How A Rated-R Movie Tricked The World Into Loving Sci-Fi Nerds

- Judd Apatow Makes Freaks And Geeks A Priority

- How The 40-Year Old Virgin Hypnotized The World

- The Origins Of Andy Stitzer

- 1980s: When Nerds Were The Disease And Punching Was The Cure

- 1990s: The Steve Urkel Effect

- 1999: The Early Foundations Of Nerd Acceptance

- 2004: The Last Gasp of a Nerd-Hating Culture

- Now: The Current State Of Nerds

- Elon Musk Owes It All To Steve Carell

The year is 2004, and audiences are buying tickets to have a laugh at the expense of a boy named Napoleon in the movie Napoleon Dynamite. The film becomes a box office hit, and no one minds that its protagonist is pitiable. He’s a nerd, part of a cultural group everyone feels comfortable subjecting to ridicule. No one wanted to be a nerd like Napoleon, and that was the point.

The year is 2006, and being a geek is so cool that a model named Olivia Munn begins portraying herself as a nerd. It may or may not have been true, but it works, and diving into the world of nerds helps make her famous. Munn builds an entire career out of being a desirable dweeb, and soon, the world is filled with attractive celebrities claiming geek status.

Modern readers may have a hard time imagining a world in which geeks and nerds weren’t accepted, but that was the norm until 2005, when one movie changed everything people thought about them.

The 40-Year Old Virgin was that inciting movie, and this is the story of how it tricked the world into thinking there’s nothing wrong with nerds. You haven’t been brainwashed, you’ve been screenswashed.

Judd Apatow Makes Freaks And Geeks A Priority

The world changed in 2005. By 2006 American culture was geek culture, a place where it would surprise no one to hear the captain of the football team talking about his newly purchased lightsaber.

What happened between Napoleon Dynamite in 2004 and the rise of the aforementioned Olivia Munn in 2006 wasn’t organic. People didn’t change their minds about nerds because they suddenly realized they should be nicer to them. The world changed its mind about geeks because it was tricked into loving them by a singular piece of entertainment called The 40-Year Old Virgin.

Released in 2005, The 40-Year Old Virgin was the first movie directed by comedian-turned-filmmaker Judd Apatow. In 1999, he’d previously tried to make a TV series around the idea of lovable and sympathetic nerds. The show was called Freaks & Geeks, and it was critically acclaimed. Those rave reviews didn’t matter. Audiences were so turned off by the concept that the series was canceled after airing only a handful of episodes.

Judd Apatow didn’t give up. He found a new way to deliver his pro-geek message when he later teamed up with comedic actor Steve Carell and, with him, convinced Hollywood to greenlight an R-rated comedy called The 40-Year Old Virgin.

“I thought of it as Freaks and Geeks 20 years later if one of them never had sex,” he told GQ. “That was my secret thought as I made the movie.”

He’d learned important lessons from his past failures. This time Judd took a less obvious approach to sympathetic geekiness. He did it with a trick, a trick that transformed nerd-hating viewers into full-on nerd lovers.

Andy Stitzer is the movie’s main character, and he is exactly what the movie’s title says he is. He also has a massive collection of vintage action figures and knows a few magic tricks. He may not wear glasses, but Andy’s not only a 40-year-old virgin, he’s also a 40-year-old nerd.

In the minds of those buying tickets to see it, The 40-Year Old Virgin was supposed to be another piece of nerd abuse comedy in the style of Napoleon Dynamite. That trick is the source of the movie’s screenwashing success. The 40-Year-Old Virgin is designed to appear as if it’s mocking Andy while quietly making the audience root for him. Then, when they least expect it, they fall in love with him.

The Apatow comedy’s name sells the idea of promised geek mockery, and the movie’s trailers only further relayed this notion by focusing on The 40-Year Old Virgin’s lead character making a fool of himself while getting his chest waxed. The film’s marketing wisely avoided anything too heartfelt.

A chest-waxing laugh at the expense of Andy Stitzer isn’t all the movie is and wasn’t something it could have been. The film’s chief nerd is played by Steve Carell, an actor incapable of being unlikable. That’s exactly what Judd Apatow wanted.

How The 40-Year Old Virgin Hypnotized The World

Audiences walked into The 40-Year Old Virgin ready to laugh at Steve Carell’s Andy Stitzer. By the time they walked out, they were laughing with him.

In the minds of viewers, Andy became the kind of guy you’d love to be friends with, the kind of guy you’d like to see date your daughter. He became that person not because he changed but because you did. He doesn’t stop building scale replica models or staying up late playing tuba. Andy Stitzer is the same nerd at the end that he was at the beginning, except with a new confidence built up by realizing people care about him.

Andy’s journey is not one of abandoning his nerdiness to become someone else. He doesn’t become Stefan Stitzer to get the girl. Andy’s arc in The 40-Year Old Virgin is completed when he learns to accept himself as he is, and then surrounds himself with people who love him, geekiness and all.

The 40-Year Old Virgin was a huge hit. The movie opened at number one and stayed there for two weeks. It remained in the top two for five weeks. Those who saw it went back with their friends. Those who didn’t see it likely heard the news media talking about it and saw lovable Steve Carell out there, front and center, as the movie’s prototypical nerd.

The movie went on to spawn a whole generation of Judd Apatow-related movies, like Knocked Up and Forgetting Sarah Marshall. Steve Urkel was no longer the nerd image in people’s heads. Judd Apatow’s movie and Steve Carell’s warm, friendly character took root there instead.

It doesn’t matter whether you’ve seen the film. The movie’s success created a huge cultural shift by reprogramming the brains of the people who saw it. Those people then took that programming with them and spread it to others. The nerd positivity The 40-Year Old Virgin designed spread through American culture like a mind virus, carried to new, impressionable brains by talk shows and other pieces of corporate entertainment rushing to duplicate that success. The entertainment media battled each other to be on the cutting edge of what Judd Apatow had now convinced them was a new trend.

Maybe your first indoctrination was watching Superbad or a documentary on the dangers of bullying. It doesn’t matter where you got the idea that nerds weren’t so bad; it was The 40-Year Old Virgin that put it in your head.

The Origins Of Andy Stitzer

None of it would have happened if Apatow hadn’t served as a producer on a previous R-rated comedy called Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy. Steve Carell has a supporting role in that film. He steals every scene he shows up in.

Judd Apatow was so impressed he told Steve to call him, if he ever had an idea for something he wanted to do. Steve Carell did. He’d come up with a character to use in sketches with the legendary Second City Improv group and told Apatow about it. Carell told GQ: “It was about a guy playing poker with his friends, and they were all telling really dirty sex stories, and slowly, you realize that he’s a virgin, and his stories make no sense.”

That sketch would eventually become one of the funniest and best scenes in the movie, but as Apatow and Carell fleshed out the concept, they realized they wanted to do something more than a cheap sketch. They wanted people to understand their geeky virgin as a real person.

Apatow told GQ: “We learned from our research when we read a lot of blogs on the internet from virgins that they are all just nice, shy people, and they weren’t odd. There wasn’t any big joke to it.”

They took the same approach with Andy’s friends who, in a standard movie about an awkward virgin might have mocked him or bullied him. But Judd Apatow tells Entertainment Magazine: “At first glance, these guys embody every bad, misogynistic attitude toward women…but deep down, they are sweet guys with the best of intentions who cover up their own terror with horrible theories on women.”

The movie never tries to hide Andy’s quirks. Apatow says, “Andy has turned his energy—decades of pent-up sexual energy—into his other interests. So he’s amassed a rather large collection of action figures and video games. He’s not exactly a hermit, but he’s an introvert who keeps to himself amidst his collection of stuff.”

Andy is a good, kind, lovable person and also a legitimately introverted, card-carrying geek who keeps his action figures vintage and knows an assortment of magic tricks. He’s the kind of guy you’d have met at the San Diego Comic Con, in the early days before attending became acceptably cool.

Making Andy sympathetic may have been Apatow’s intention, but the studio funding his film was still stuck in a mindset that had them thinking of nerds as less than human. After only five days of filming, Univeral Pictures got cold feet and tried to kill the movie.

Maybe they’d seen Napoleon Dynamite too many times and weren’t ready to take off their nerd-hatred colored glasses, but Universal decided Steve Carell’s character looked like a serial killer and wanted nothing to do with it. Apatow and his team calmed them down, allowing the movie to resume filming.

When Nerds Were The Disease And Punching Was The Cure

Before The 40-Year-Old Virgin, nerd perceptions were very different. To prove that point, take a trip back in time with me to the release of the movie Back to the Future. Arriving in 1985, the film features a prototypical nerd character named George McFly.

When the movie starts, George McFly is an adult nerd, and as a result, the movie assumes he’s also a total loser. By the time Back to the Future ends, his character arc is completed only when he gives up his nerd tendencies and starts acting like the kind of cool, confident guy who punches assholes in the face and plays tennis on the weekend.

Changing George McFly from a nerd into a tennis-playing tool is, in a sense, the entire reason for Marty McFly’s adventure. Because, after all, who’d want a nerd for a father? No thanks. Get that man a doubles partner.

It worked because this was the ideology eighties audiences were most comfortable with. No one paused their VCR and asked, “Hey, what’s wrong with being a nerd?”

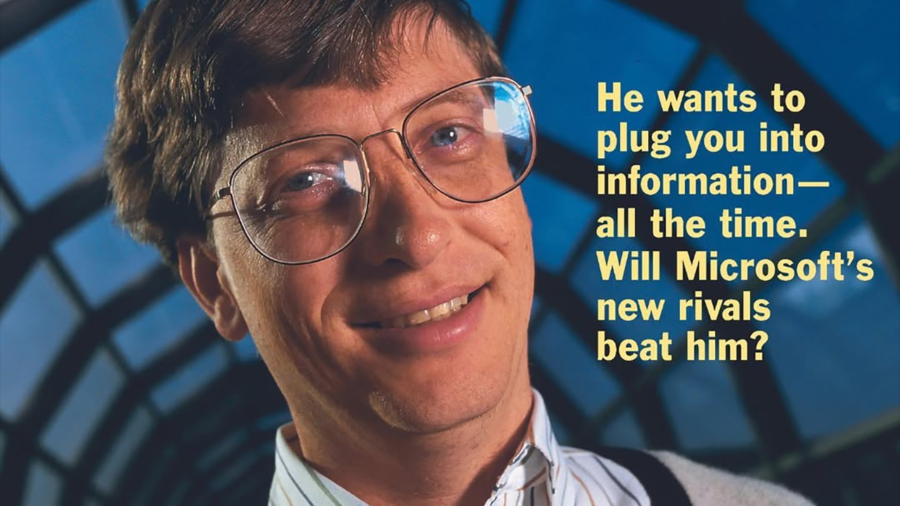

The best example of America’s pre-2005 anti-nerd bias is found in the most famous nerd of all time: Bill Gates.

Long before Elon, Bill Gates was famous for being a geek, and also famous for being uniquely hated. He was frequently criticized for overly aggressive business practices and being evasive when faced with government scrutiny. The view of the general public in the 80s and 90s, when it came to Bill Gates, was that he was a creep who spent way too much time reading books and stole everything he’d accomplished. He was also viewed as the prototypical modern representation of a nerd.

Gates was once so hated that it became unsafe for him to go out in public. It culminated in 1998 when, while walking down the street, he was attacked and hit with a pie in the face by a French activist, Noel Godin. The act was seen as a protest against Bill’s monopolistic practices, and the public didn’t exactly feel bad for Bill when it happened. Most felt he had it coming.

While he’s still unpopular in some circles, most now view him favorably. Gates has become Geek Jesus, a super smart savior traveling the world dispensing vaccines to sick kids.

The Steve Urkel Effect

Not all nerds were hated in that pre-2005 world. Hated or not, none of them were respected. Few figures embodied this form of anti-nerd bigotry better than Steve Urkel.

Steve Urkel was one of the most popular characters in television history. In the early 1990s, people quoted him, dressed as him for Halloween, and bought thousands of talking Steve Urkel dolls.

As played by Jaleel White on the sitcom Family Matters, Steve Urkel was loved specifically because people enjoyed mocking him. Laughing at Steve made viewers feel better about themselves because at least they weren’t like him.

In one of the later Family Matters seasons, Steve develops a magic formula called “cool juice” that transforms him into a less intelligent, more suave version of himself called Stefan. When it happened, the audience did not bemoan the loss of their beloved nerd. Instead, fans celebrated Steve’s victory over his nerdiness. In the context of the show, Stefan is rewarded for his coolness by getting the girl whose heart nerdy Steve Urkel had been trying and failing to win all along.

The most popular, long-running gag on Family Matters revolved around Carl Winslow throwing Steve Urkel out of his house. He tosses him out because Steve is an annoying nerd. It was funny every time it happened because Carl was always right. Steve was annoying, and like all nerds, he had it coming.

The Early Foundations Of Nerd Acceptance

The foundation for full nerd acceptance was laid in 1999 when corporations looked up and noticed that nerdy things were becoming exceptionally profitable.

Lines wrapped around the block for The Phantom Menace. Star Wars toys were flying off shelves, and they weren’t being sold to kids. The Matrix was the surprise hit of the decade, and the adult men in line for it looked like they’d fallen out of a Volkswagon bus on its way to a permanently single convention.

The geeks who opened their wallets for those 1999 cash cows did not gain acceptance by rote of their numbers. If you were one of many bespectacled Star Wars fans who slept outside a movie theater that year, there’s a good chance a carload of frat boys drove past, rolled down their windows, stuck out their backsides, and shouted, “Nerds!” at you and your fellow line campers.

The local news was also present at those Jedi campouts. Their aim was to cover the massive popularity of geek sci-fi properties with a strongly slanted “hey, look at these crazy weirdos!” angle. Making fun of nerds got them ratings.

Those big companies that noticed the profit potential built up inside those line-standers spent the next few years greenlighting more geek-friendly projects. Slowly, as movies like The Matrix gained more widespread acceptance, the cultural stigma against geekery began to soften. It didn’t dissolve.

The Last Gasp of a Nerd-Hating Culture

When released in 2004, Napoleon Dynamite, for all its uniqueness, was the last gasp of a nerd-hating culture. The character was popular in the same way Steve Urkel was popular. Audiences loved laughing at him, but no one was interested in laughing with him.

Without the built-in negative feelings American culture had about nerds, it would not have been OK to laugh at all. Instead, the audience might have felt sorry for Napoleon, who lives a horrible and sad life deserving of pity, not scorn.

Napoleon Dynamite’s a nerd, so no one cared. That left the 2004 audience members buying tickets to his movie, free to laugh at him.

The Current State Of Nerds

Being a geek is now chic. Nerds have gained such broad acceptance that much of our world has been realigned to protect them. Anti-bullying campaigns are the standard in public schools, and social media is filled with super-attractive celebrities telling stories about how they were abused and bullied in high school before they got hot.

Stories of past nerd suffering make the tellers more popular, or they wouldn’t share them. Take the time to investigate, and you’ll likely find most of them aren’t true.

It doesn’t matter. When an attractive would-be star declares themselves a nerd, it’s viewed as a good marketing move. Entire YouTube empires have been built off that simple premise. It may not last forever, but in 2025 things have never been better for the word nerd.

Elon Musk Owes It All To Steve Carell

If pop culture’s view on nerds before 2005 was embodied by Steve Urkel, then in a post-2005 world, it is best embodied by Tony Stark. Stark is the smartest and quirkiest character in the Marvel Universe. Like the many other fictional and real-life nerds who came before him, Tony talks too fast because his mouth can’t keep up with the ideas in his head.

Tony’s every bit the nerd Steve Urkel is, except he’s handsome, rich, and can get any woman he wants without the aid of cool juice to unleash his inner Stefan. And, of course, Tony Stark only wears glasses when doing so will give him superpowers or make him look awesome.

If pre-2005’s real-world nerd representative is best embodied by Bill Gates, then in a post-Apatow world, he’s been replaced by Elon Musk.

Where Gates repulsed everyone who encountered him, Elon Musk is the toast of the social media and the podcasting world. Elon’s notorious for the number of beautiful women he juggles, and he’s the kind of celebrity most Hollywood stars only dream of being.

There’s no doubt about it: Elon Musk is a nerd. He talks too fast, slurs his words, plays video games, geeks out about space, and has the posture of a middle-aged writer. Yet, everyone wants to be him. If they don’t, it’s only because they’re jealous.

Things have changed, and nerds, at least the good-looking or rich ones, have Judd Apatow’s artful screenswashing in The 40-Year-Old Virgin to thank for it. When it comes to the less physically fortunate nerds out there, maybe things are as bad as ever. Except now they’ve lost their identity to the likes of hunky Henry Cavill (who loves nerdy games and building computers).

If Henry Cavill is now a nerd, then I suppose we’ll have to come up with a new word for the poor, introverted, fat kid still living in his mother’s basement and hoping to meet a supermodel who won’t expect him to look like Superman. Sorry kid, it’s probably not going to happen. Here’s to the losers, one and all.

Login with Google