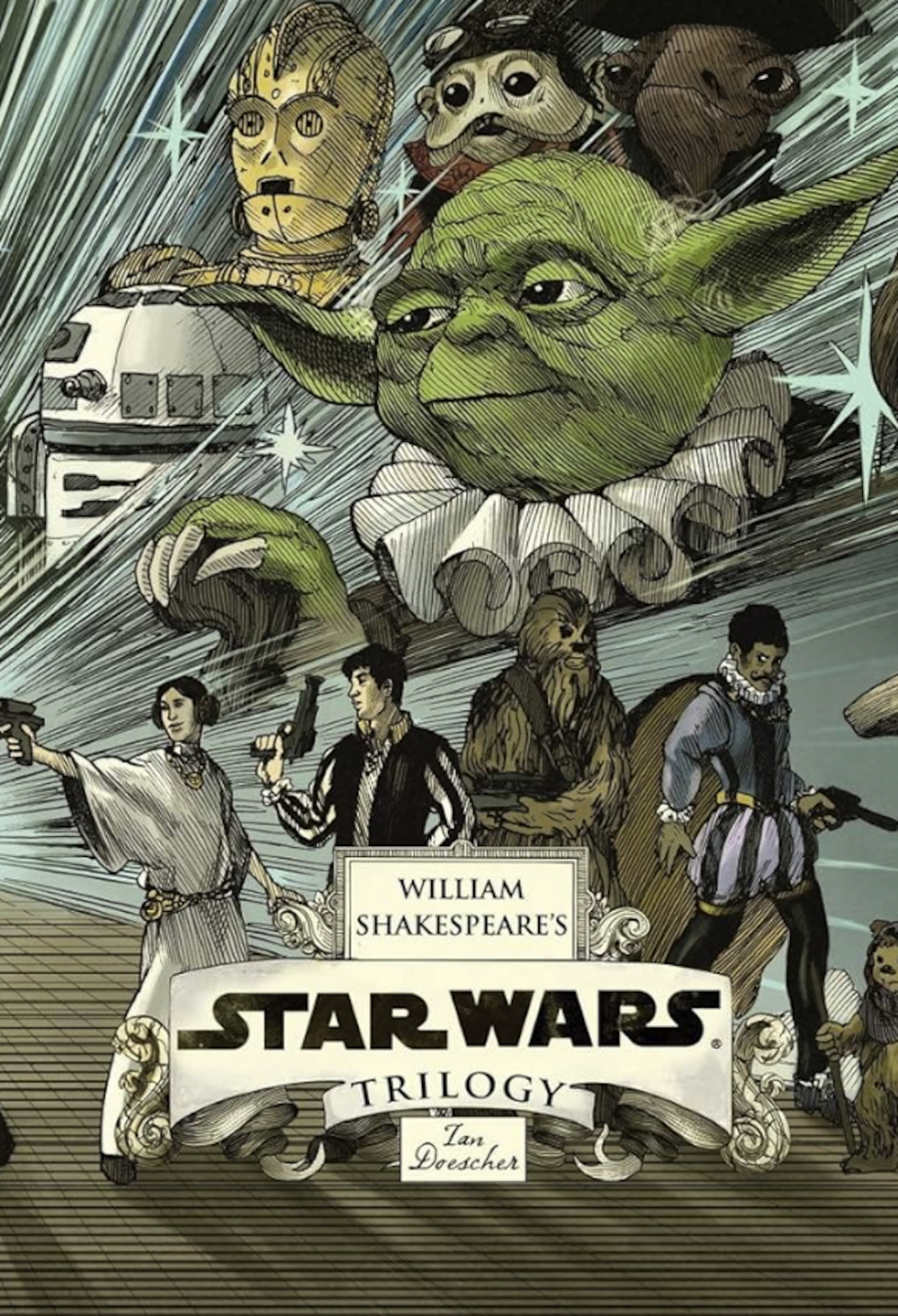

William Shakespeare’s Star Wars Book Review

Since Seth Grahame-Smith’s hit 2009 novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies firmly placed off-kilter literary mashups into the public consciousness, the sub-genre has seen some truly interesting titles come to light. We’ve had Ben H. Winters’ steampunk Android Karenina and Peter Clines‘ H.P. Lovecraft-inspired Robinson Crusoe (The Eerie Adventures of the Lycanthrope), among others.

Now, you might not think the greatest mashup of all time would come from a musician/creative designer for a marketing research agency, but Ian Doescher has created a doozy of a first novel in William Shakespeare’s Star Wars, a nearly seamless fusion of two classic influences that aren’t nearly as discordant as they initially seem.

In his William Shakespeare’s Star Wars afterword, Doescher cites Joseph Campbell’s seminal The Hero with a Thousand Faces as the connective tissue between the Bard and George Lucas. Campbell’s mythological archetypes were strongly influenced by Shakespeare’s literary oeuvre, and in turn, Lucas openly crafted the screenplay for Star Wars with Campbell’s storytelling philosophies in mind.

What Doescher has done is insert himself as the narrative-altering middleman, reimagining Lucas’ creation with 17th-century aplomb.

While Lucas’ visionary cinematic style isn’t the most obvious choice for the stage, where blaster battles and enormous spaceships aren’t easily portrayed, Doescher manages to put memories of the film in the back of the mind, replacing them with a feast of hyper-clever, reworked dialogue. I’d wager it’s exceptional enough to fool younger Star Wars fans into believing this is the original source material for the film.

From William Shakespeare’s Star Wars opening scroll, which ends instead of begins with “In time so long ago begins our play, In the star-crossed galaxy, far, far away”—to the final, medal-awarding proceedings, Doescher leaves no stone unturned, capturing every pivotal moment while adhering to iambic pentameter the entire time. The metered translations alone make this book seem like a more intense mental task than writing the film’s original screenplay.

Not only are all of the film’s best bits handled with an adroit touch, but in William Shakespeare’s Star Wars Doescher imbues the work with foreshadowing and subtle in-jokes—more often than not in the form of character asides—that could only be made with prior knowledge of the entire first trilogy. But if this is cheating, then honesty is a failure. What it does is solidify a yearning for the author to continue his efforts and adapt the next two films.

These asides, and the chorus beats, are where William Shakespeare’s Star Wars differs most significantly from the film, both as a way of filling in for onscreen action that has no stage equivalent, and in character exposition that may not be obvious for people that haven’t seen Star Wars. (Although I can’t imagine anyone reading this before watching the flick.)

William Shakespeare’s Star Wars digressions convey Obi-Wan’s moral values where Luke is concerned and offer clues to the boy’s parentage without spelling anything out explicitly. This literary technique also allows for R2-D2 to finally have a real voice, one that belies his good-natured ways. He’s quite the snarky little bot. C-3PO somehow becomes even more neurotic and anal retentive through his internal monologues.

Doescher refers to the two droids as equivalents to Hamlet‘s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in terms of their outsider take on the narrative. While that comparison makes sense, there is a scene that centers on a banal, meandering conversation between two Stormtroopers, that brings to mind Tom Stoppard’s amazing play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.

All of the film’s most iconic beats are recreated in splendidly wordy glory in William Shakespeare’s Star Wars. There’s Darth Vader’s Force-choking, the Cantina scene where we meet Han Solo in all his cocky avarice, and the garbage compactor sequence.

For some reason, Han and Luke vying for Leia’s attention reads as much more romantic when told in this style, even as Han’s ego threatens to weigh down every page. While the battle on the Death Star loses some vitality, reading more as a transcription than an actual ongoing event, it’s the only time I felt that way during the entire book.

This brings us to the very brief portion of this review, where I mention things that don’t work so well. Since I already mentioned the Death Star destruction, the only real complaint I have is that Vader is only a shadow of the monstrous pillar of evil his is on screeen.

It feels like he justifies his thoughts and actions far more often than he’s just doing evil shit because that’s just who he is. Granted, a little sprinkled humor manages to humanize him, but that’s not how I like him. Anyway, it’s hardly a real complaint, and he’s still an interesting character.

William Shakespeare’s Star Wars itself is a brisk 176 pages, so while I would love to fill this review with quote after quote, giving away all the book’s secrets – such as how Doescher handles the question of “Who shot first?” – all it takes is an hour or two of reading to figure everything out for yourself. And you definitely should, as this has easily set a new benchmark for pop culture literature. Hopefully, it won’t be long before the novel’s actual productions are performed all over the world.

“The Force, it shall be with thee always.” Similarly, this book will be with me for quite a while, at least until Doescher hopefully provides us with his versions of The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. I might have a talk with Jabba about sending a few timely threats Doescher’s way…