The Sun Is Acting Extremely Strange But We May Know Why

Scientists think they know how the Sun generates extreme heat.

This article is more than 2 years old

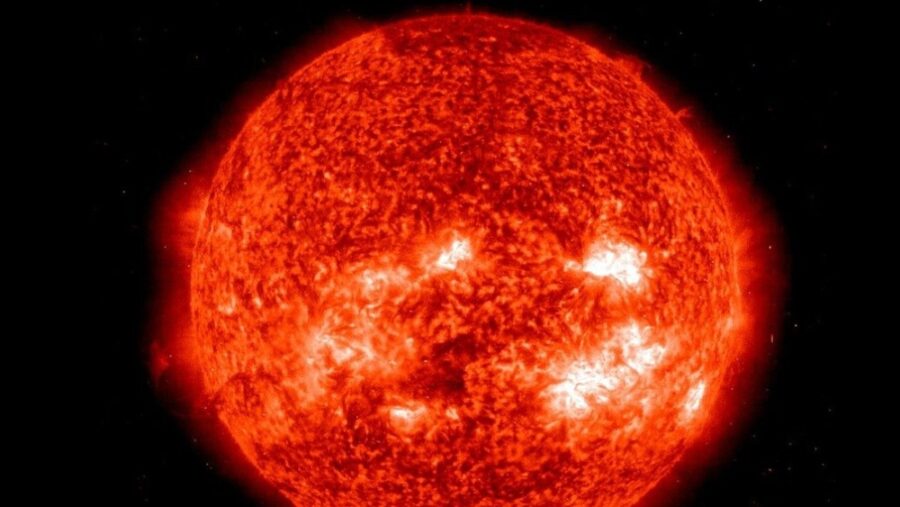

The sun baffles scientists with burning questions, but the European Space Agency has taken a huge step forward in studying the heart of Earth’s solar system. As reported in ScienceAlert, the ESA’s Solar Orbiter is capturing the most detailed images of the sun ever recorded. Its findings support a long-held hypothesis that small magnetic field reconnections account for the Sun’s immense heat.

At its surface, the Sun burns at a raging 5,500 degrees Celsius, or 9,932 degrees Fahrenheit – normal for a star of its size and kind. What has long puzzled scientists is that the temperature of the sun’s atmosphere is even hotter, and it heats up more the further from the surface you get. The corona, the outermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere, caps at 2 million degrees Celsius.

This phenomenon is called coronal temperature inversion. Astronomers have long speculated that the energy produced by small magnetic field reconnections could be the source of the corona’s extreme heat.

The sun, like many stars, is made largely of plasma. It is a swirling mass of charged fluid that generates immense magnetic fields. In the photosphere, the innermost atmospheric layer of the Sun, lines of magnetic fields twist together, break apart, and reconnect.

When magnetic fields connect, they release a massive burst of energy. These connections cause things like solar flares, and they are a well-observed phenomenon when they happen on a large scale. Smaller magnetic field reconnections in the photosphere have only been theoretical.

Enter Solar Orbiter. This craft is making a series of perilous trips around the sun to capture high-resolution photography that details what is happening in the photosphere more clearly than has ever been possible. Its findings have finally provided astronomers with observational evidence that small-scale magnetic field reconnections are always happening on the Sun.

The craft observed a magnetic reconnection that was only 242 miles across, just a little less than the length of the Grand Canyon. That is huge on the Earth, but tiny on the Sun.

At the point of reconnection, called the null point, the intensity of the magnetic field drops to zero. Its temperature during this period is 10 million degrees Celsius.

For about an hour, that temperature is held as energy, and mass spews outward 80 kilometers per second. And that is what scientists call “gentle” reconnection. Null points can occur with far more violent and explosive results that are maintained for a far shorter time – about four minutes.

The energy launched outward from the Sun by these reconnections could account for the intense heat in the star’s outer atmosphere, and scientists now theorize that more of these connections are taking place at an even smaller scale. As Solar Orbiter continues its mission, astronomers hope to get a closer look at this phenomenon.

There is still a lot of work to be done in solving the mysteries of the Sun, but the ESA’s Solar Orbiter is taking scientists’ understanding of our home star to a whole new degree.