Scientists Find Mysterious Deep Space Radio Signal Broadcasting For 30 Years

Typically speaking, rotating neutron stars (known as pulsars) are known to emit radio waves at regular intervals, ranging from seconds to milliseconds. When these neutron stars approach the end of their lifecycle, they slow down and are no longer referred to as pulsars, but rather get categorized as magnetars. According to The Conversation, scientists have been baffled by the discovery of a pulsar (or magnetar) that has been emitting radio-waves in a 22 minute cycle for over 30 years.

This discovery is changing our understanding on the lifecycle of neutron stars because when a pulsar slows down and becomes a magnetar, its radio emissions should only be detectable for a few years at most, not a few decades. In other words, we’re witnessing an outlier when we compare our current understanding to what’s being discovered.

Scientists have been baffled by the discovery of a pulsar (or magnetar) that has been emitting radio-waves in a 22-minute cycle for over 30 years.

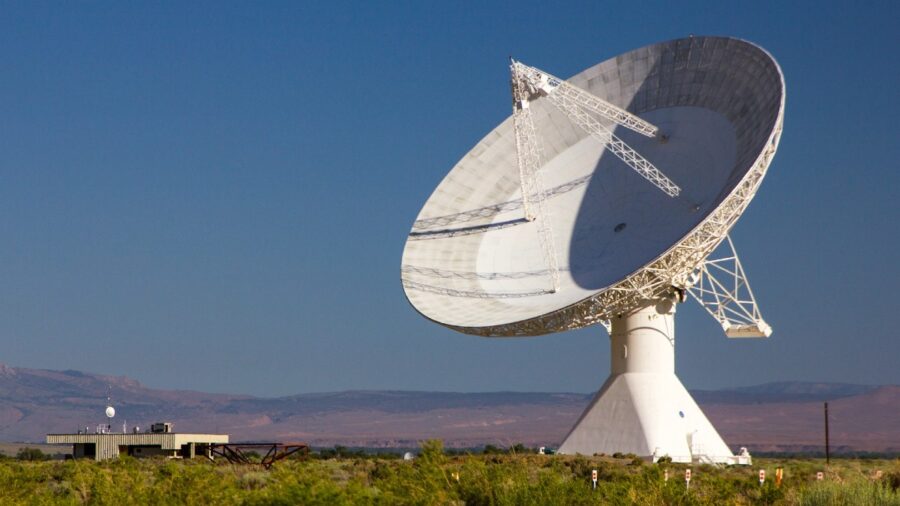

When researches combed through the data that was archived by The Very Large Array telescope in New Mexico, they stumbled upon a magnetar (now referred to as GPM J1839−10) that has been active since 1988, which raises a lot of questions about its origin and prolonged visibility.

When compared to other pulsars and magnetars in the database, it’s evident that this over 30-year-old, but newly discovered, magnetar has something else going on. Based on their research, scientists have asserted that each pulse is typically produced by its source every 1,318.1957 seconds, which is what we currently believe to be the average pulse duration in most cases (give or take a tenth of a millisecond).

What’s more, when a pulsar slows down, and becomes a magnetar, it’s a clear indication that we’re approaching the end of its lifecycle, and will stop emitting radio-waves entirely.

When compared to other pulsars and magnetars in the database, it’s evident that this over 30-year-old, but newly discovered, magnetar has something else going on.

GPM J1839−10, however, boasts a 5-minute pulse, and a 17-minute gap in between pulses, which is causing researchers to question how, why, and whether the source itself is actually a pulsar, magnetar, or something else entirely. Even if this unique discovery is emitting radio-waves in a similar fashion to other pulsars and magnetars, it’s long life defies our current theories and understanding of pulsars.

In theory, GPM J1839−10 could be the key to better understanding if neutron stars have a whole other phase in their lifecycle that is unique from what we currently know about pulsars and magnetars. Radio astronomer Natasha Hurley-Walker, who is the lead author of the study, hopes to find other magnetars that are operating similarly, so this anomaly can be compared to other data points.

Are Aliens Involved?

And if you’re getting excited about the possibility of extra-terrestrial life being responsible for such a strange celestial emission, we’re here to disappoint you just a little bit. When pulsars were first discovered by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and her colleagues in 1967, they also made this assumption.

In fact, they even named the first pulsar that they discovered “LGM 1,” which is an acronym for “little green men.” But given the widespread presence of pulsars in our known universe, and how consistent and uniform most of them are in their emission of radio frequencies, it quickly becomes apparent that pulsars are simply a part of nature that we’re still trying to fully understand.

Even though we’re a bit bummed that we still haven’t made contact with other intelligent life forms in our universe, we should still be excited about the possibility of a new pulsar variant that will be instrumental developing a better understanding of how our universe operates.