Black Holes Burping Out Stars, Stumping Scientists

Black holes have long stumped astronomers with their unpredictable behavior. New research states that half of all these strange regions of space that devour stars exhibit a peculiar habit of “burping up” their remnants years later. The discovery was made by a team of astronomers who dedicated years to observing black holes involved in Tidal Disruption Events (TDEs).

Scientists have discovered that half of all black holes will expel remnants of stars they destroyed years earlier.

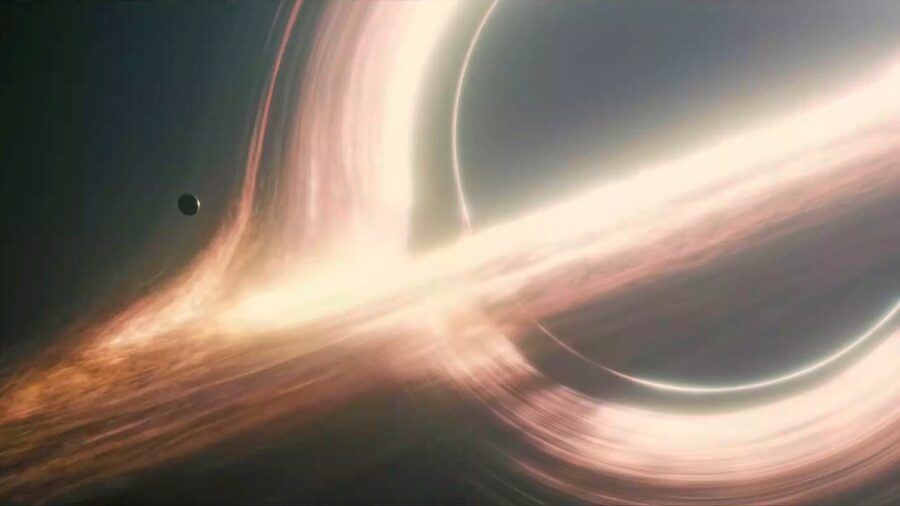

According to Live Science, TDEs occur when stars venture too close to black holes, subjecting themselves to gravitational forces generated by these cosmic behemoths. The outcome is a process known as “spaghettification,” where the star is stretched and squeezed until it’s ripped apart in a matter of hours, accompanied by a brilliant flash of electromagnetic radiation.

The aftermath of a TDE is a spectacle in itself. Some stellar material from the unfortunate star is flung away from the black hole, while the rest merges into a thin, frisbee-like structure known as an accretion disk. This disk gradually funnels matter back toward the voracious black hole. In its early stages, the accretion disk is unstable, causing matter to move around, generating radio waves.

However, traditionally, astronomers have focused their observations on these star-eating black holes for only a few months following the TDE. The study, which extended their observations to hundreds of days, found that in almost 50 percent of cases, black holes “burped” out stellar matter years after the initial event.

“I call it a ‘burp’ because we’re having some sort of delay where this material is not coming out of the accretion disk until much later than people were anticipating.”

-Yvette Cendes, Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics research associate

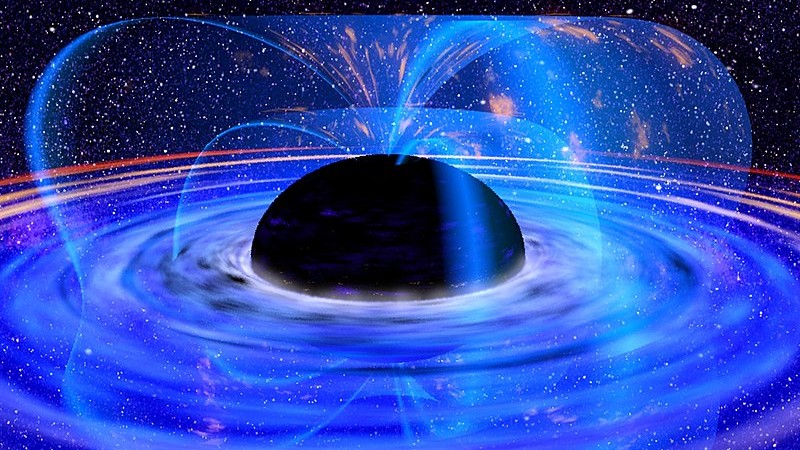

Study lead author Yvette Cendes, a Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics research associate, likened this phenomenon to a delayed release of material from the accretion disk. “If you look years later, a very, very large fraction of these black holes that don’t have radio emission at these early times will actually suddenly ‘turn on’ in radio waves,” Cendes said.

“I call it a ‘burp’ because we’re having some sort of delay where this material is not coming out of the accretion disk until much later than people were anticipating,” Cendes continued. Despite this discovery, the scientific community remains puzzled about the exact cause of these late emissions from black holes. The mystery deepens when considering computer models that have been used to simulate TDEs.

These models have traditionally terminated just weeks after the star’s destruction. The new findings suggest that these models need substantial updates to account for the unexpected behavior. In two cases, black holes emitted radio waves that peaked, faded, and then surged again, defying previous expectations.

Black Holes Devouring Stars

Black holes have been eating stars for billions of years. However, the first observed instance was in 1999, when astronomers discovered a tidal disruption event in a galaxy about 215 million light-years away. Since then, astronomers have observed many TDEs, which have become an essential tool for studying black holes.

In some cases, black holes take only a year to eat a star; in others, they can take more than a decade to consume a star. The gravitational forces don’t limit their impact to stars alone. Nearby planets and celestial objects within the star system can be perturbed, leading to ejections or collisions from the system.

Black holes can also produce energetic jets of material that shoot out from their poles at nearly the speed of light. These jets are powered by the accretion disk and significantly influence the surrounding environment. It remains to be seen if the new findings help further our understanding of black holes going forward.