The Return Of The Jedi True Story Heist That Deserves To Be Its Own Movie

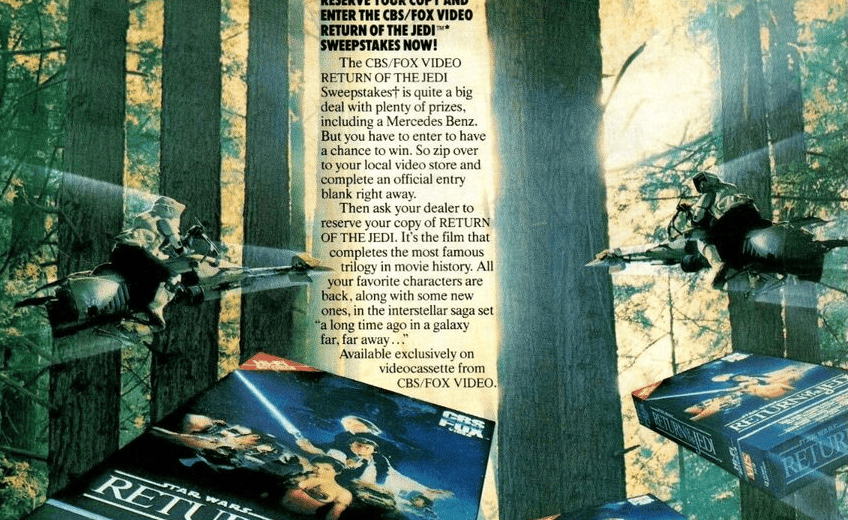

Piracy refers to the illegal copying, distribution, and use of copyrighted materials, which also includes movies. In today’s digital age, the contents are typically shared via the World Wide Web, and obtaining them and releasing them in the wild is as easy as ripping a Blu-ray disc or stealing the content via communication technologies. But that wasn’t always the case; piracy, just as many technologies, used to be analog, and Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi was physically stolen several times.

The fact that piracy used to be analog meant that those who practiced it had to steal the physical copy of the movie to turn it into illegal home video cassettes to be shipped around the world. Return of the Jedi was actually stolen six times—documented theft—from theaters in three states and in Britain. The objective of these cases was to turn these 35-millimeter prints into illegal home video cassettes, and several of these cases actually included armed heists in which the film reels were stolen from theaters at gunpoint.

Two perpetrators in clown masks stole a print of Return of the Jedi at gunpoint from the projectionists.

One such incident happened in Santa Maria, California, where two perpetrators in clown masks stole a print of Return of the Jedi at gunpoint from the projectionists. Prior cases include thieves breaking down theater doors in Hastings, England, and Sherman Oaks, California. In South Carolina, the movie was inexplicably missing, and theft happened in Overland Park, Kansas, where the projectionist transferred the movie to a transport container, as per instructions of the thief who held him at gunpoint.

The projectionist of that particular case wasn’t harmed, but the thief, later identified as 18-year-old Larry Dewayne Riddick, Jr., had fled the scene with the equivalent of a king’s ransom. All these cases would make for heist movies in their own right, particularly the case of Larry Dewayne Riddick, Jr., who stole the reels at gunpoint, hid them in the basement of his family home, and later tried selling Return of the Jedi to a local video store for a higher price. Most video stores that resorted to piracy usually conspired with illegal film labs that transferred the prints to VHS cassettes.

Larry Dewayne Riddick, Jr… stole the reels at gunpoint, hid them in the basement of his family home, and later tried selling Return of the Jedi to a local video store for a higher price.

Back in the day, a copy of a high-profile release would go for as high as $200 per cassette, but Riddick didn’t have the means of transferring the film to VHS, so he sought bulk payment. The owner of the video store reported him to the FBI, and the young man was arrested by two agents posing as a couple interested in buying the Return of the Jedi reels for $10,000—equivalent to approximately $30,600 when adjusted for inflation.

For younger readers, movies were usually shot using 35-mm or 70-mm film, which was later transferred to VHS cassettes that required videocassette recorders to play and reproduce the audio/video content. In the context of piracy, recording content from AV sources was exceptionally easy, including copying VHS cassettes. However, transferring movies like Return of the Jedi from reels onto cassettes required specialized equipment, so most pirated who managed to steal the reels had to sell them to specialized labs to turn a profit.

Pirating content is exceptionally easy now, and while the practice isn’t legal—and thus, we don’t advocate for it—we’ll say that it’s currently at the forefront of media preservation. As for the Return of the Jedi thefts, they truly deserve the movies of their own, as they would detail the journey and various hurdles people had to go through to get their hands on a physical copy. We’d also like to recommend 2023’s Tetris, starring Taron Egerton, as it depicts the events around the race to license and patent the video game Tetris from Russia during the Cold War.

Source: New York Times