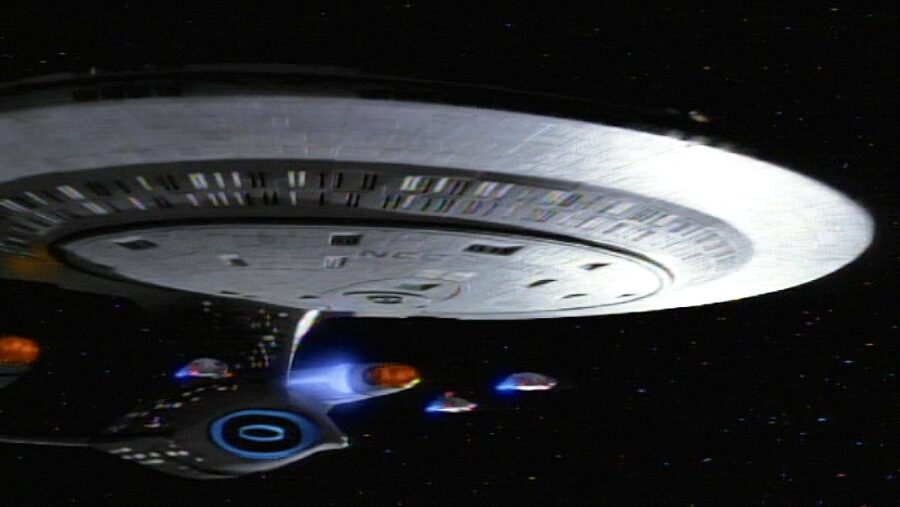

The Best Star Trek Show Gets One Thing Fatally Wrong

One of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine‘s weak spots is how the Prophets and the show’s handling of spirituality changed for the worse over the course of its seven seasons. The Prophets went from being aloof, distant, and utterly ineffable aliens to calculating deities who saw themselves exactly the way the Bajorans always had. This helped make good stories, but it steered DS9 too far from the spirit of Star Trek.

Challenging Secular Star Trek

DS9 is the first Star Trek show to feature any regular cast members — Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor), Quark (Armin Shimerman), and Odo (René Auberjonois) — who not only weren’t a part of Starfleet or the Federation, but wanted nothing to do with either. That, and the premise, forced DS9 to challenge the idea that the Federation way is always the right way. This is no more evident than in how the series handled the very notion of spirituality.

Until DS9, you get the impression that most if not all of the heroes we meet in Star Trek are either atheist or agnostic. Characters like Patrick Stewart‘s Jean-Luc Picard, for example, are completely tolerant of others’ religious or spiritual beliefs, but in conversations about the potential existence of God, he treats the idea as quaint at best, and inherently dangerous at worst. That’s exactly how Avery Brooks’ Ben Sisko reacts when confronted with Bajor’s religion in the DS9 series premiere, but that begins to change.

The Prophets Did Not See Themselves As Gods

When Ben Sisko makes first contact with the Prophets in “Emissary,” while it’s immediately understandable why such beings could be seen as gods, the Prophets themselves make no claim to godhood. They are so incomprehensible to humans that they are forced to communicate with Sisko through the shapes of other characters they find in his memories. We soon learn they do not even share our perception of linear time, presumably existing in the past, present, and future simultaneously.

What is it Kat Dennings’ character says in Thor? “A primitive culture like the Vikings may have worshipped (Asgardians) as deities.” It isn’t that the Prophets are gods, but that they’re so much more advanced than us that they can’t help but seem like anything but gods.

For over the first half of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, the Prophets reflect this idea. Even in Season 4’s “Accession” when Sisko and the Bajoran writer Akorem Laan ask the Prophets to confirm which one is the true Emissary, they never outright say it’s the Starfleet captain or that there is a true Emissary. They only say of Sisko, “He is the Sisko.”

Sisko Tells The Prophets To Be Gods

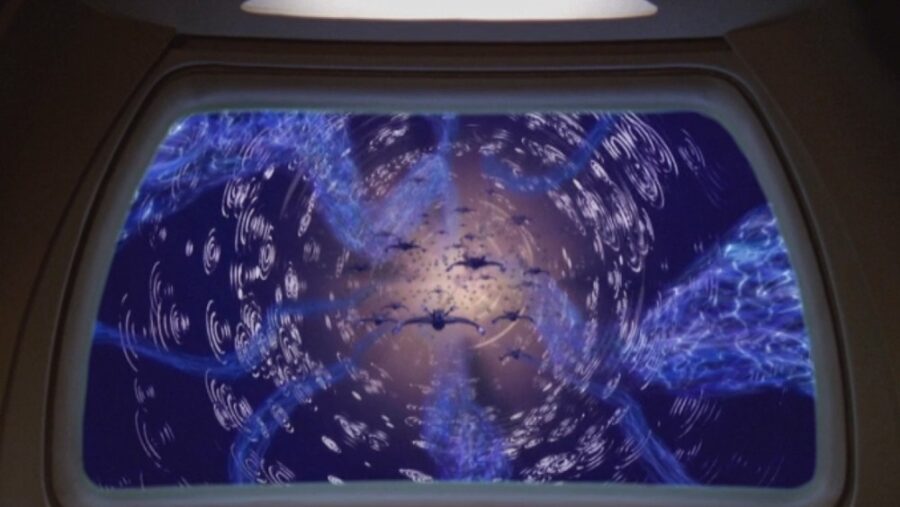

It’s in Season 6’s “Sacrifice of Angels” that we see the Prophets go from Star Trek aliens to Star Trek gods. At Sisko’s insistence, they make a Dominion invasion fleet disappear from the wormhole. We never learn if the fleet is destroyed or if the aliens simply transported them somewhere (or possibly somewhen) else.

It isn’t the fact that the Prophets take out the fleet that makes them act more as gods who have accepted their roles as gods, but the way they address Sisko. They refer to Sisko’s life as a “game” and when they finally agree to take care of the Dominion fleet, they insist on exacting “a penance.” “He is of Bajor,” they say. “But he will find no rest there.”

These are not the same Prophets from “Emissary.” Those earlier characters don’t act as if they’re treating lesser beings like chess pieces. The orbs the Bajorans have found are their way — they tell Sisko in the earlier episode — of contacting “other life forms,” not to create a religion based on them.

Yet in “Sacrifice of Angels,” these Star Trek aliens are acting like the Wadi of “Move Along Home,” except the lives they’re playing with really are at risk.

Sisko Becomes A Demigod

The final few seasons of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine see the Prophets embracing their godhood more and more, with the aliens sending Sisko visions that nearly drive him mad, and at one point demanding the sacrifice of his son Jake when the latter is possessed by a pah-wraith. Eventually we learn that Sisko himself is a child of the Prophets.

The non-linear nature of the Prophets could potentially explain any supposed plot inconsistencies — like why some of them seem ready to kill him when they meet him in the series premiere even though they presumably know he’s their child — but what’s more jarring is how they’ve changed. By the series finale, they clearly see themselves as deities as well as the final arbiters of right and wrong. The final defeat of the pah-wraiths is achieved through a mystic book — kind of a rare tool to be used to in Star Trek — and of Gul Dukat, Sisko’s mother says “he is where he belongs,” suggesting a heaven/hell like dichotomy.

Why It Matters

In their original concept of the Prophets, when it comes to the question of whether or not they are gods, the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine writers put the audience in control. Are they gods? Are they just “wormhole aliens?” It was purely up to each fan’s individual interpretation.

And with a franchise like Star Trek, which is all about asking really big questions, leaving the answers in the audience’s care is usually the right way to go. It gives fans the chance to think about certain subjects — like spirituality and the existence of a higher power — more deeply and thoughtfully than they might otherwise. But starting with “Sacrifice of Angels,” the writers kicked us out of the driver’s seat.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine remains, in my opinion, the best series of the franchise. Could the series have done without the Prophets ultimately embracing their godhood? I think so.

Could it have survived hearing Morn speak? No. No, that one they got right.