Unfaithful Sci-Fi Book Adaptations That Made Great Sci-Fi Films

Sometimes change is good.

When it comes to movie adaptations of books, 100% faithful isn’t always a good thing, nor is unfaithful necessarily a bad thing. Sometimes, a slavishly faithful transfer from a book results in a cinematic mess, whereas a film that only uses the source material as a leaping-off point can generate something fun or fascinating in its own right.

Consider Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers, which ended up satirizing many of the themes and concepts Robert Heinlein addressed with a straight face in his 1959 novel. As a result, Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers is by no means a faithful adaptation of Heinlein’s, but it is undeniably entertaining in its own right.

With this in mind, we decided to look back at some of our favorite unfaithful science fiction book adaptations that nevertheless turned out just fine.

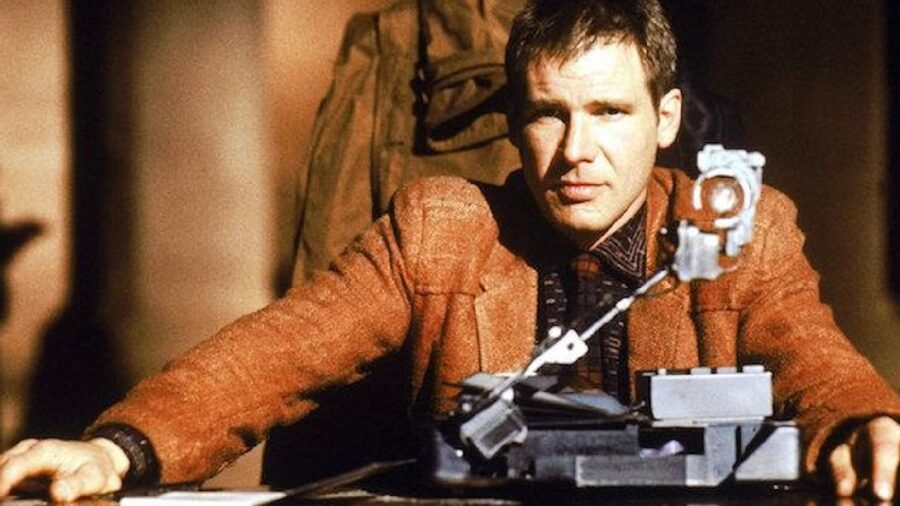

Blade Runner

Source Material: Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968)

In the Movie: Deckard is a former cop/android hunter who is convinced to take one last job to “retire” a group of rogue Nexus-6 replicants.

Several of the Nexus-6s are passing as human, but one usually reliable way of identifying an Andy is using the Voigt-Kampff test, which measures a person’s ability to feel empathy — something the androids do not possess.

It is eventually revealed that implanted memories can result in an android who doesn’t know it’s an android, something Deckard discovers after testing Dr. Eldon Tyrell’s assistant, Rachael (Sean Young), an unwitting replicant herself.

The replicants are pre-programmed with a limited lifespan, and so the group’s leader, Batty (Rutger Hauer), wants to confront his creator, Tyrell, in hopes of finding a way to get “more life.”

In pursuit of that, Batty and “basic pleasure model” Pris (Daryl Hannah) befriend kind-hearted replicant engineer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), whom they manipulate into taking Batty to see Tyrell, a meeting which does not end well for Tyrell.

During his hunt for the replicants, it is strongly implied that Deckard himself may not be human and thus may be hunting and killing his own kind. He also falls in love with Rachael. The film ends with Deckard and Rachael going on the run, hoping to make a life for however much time they have left.

But in the Book: Deckard is a bounty hunter tasked with hunting down renegade androids (“andys,” for short) in 1992 San Francisco. Earth is a thoroughly depressing place, having been ravaged by a world war that drove much of humanity to off-world colonies and wiped out many of the native animal species.

As in the movie, Deckard must track and kill a group of rogue androids advanced enough to pass for human, with some even possessing artificial memories and no knowledge of true nature. The book also follows John Isidore, a simple-minded bloke who helps the androids (and who essentially became Sebastian in the film).

As in the film, artificial animals are prevalent, but they are far more important in the book. Since biological animals are mostly extinct, owning one is a huge status symbol, and one of Deckard’s primary motives throughout the book is to acquire such an animal. (He used to own a real sheep, but after it died, he bought an artificial one — hence the title.)

In keeping with the book’s themes of empathy, Dick’s story also details “Mercerism,” a new religion that uses “Empathy Boxes” to link users into, as Wikipedia puts it, “the suffering of Wilbur Mercer, a man who takes an endless walk up a mountain while stones are thrown at him, the pain of which the users share.”

Both the book and film brilliantly explore notions of free will, what constitutes humanity, and the ethics of creating what is essentially a slave race — a nice contrast to the idea of the androids being the ones incapable of empathy.

One last fun factoid: in the book, Rachael and Pris are both the same model, so if the movie had remained faithful, either Sean Young or Daryl Hannah would have played a dual role.

Children of Men

Source Material: P.D. James’ Children of Men (1992)

In the movie: In the year 2027, the UK is basically the only world government still up and running after global infertility has driven mankind to the edge of extinction.

The country is overrun with illegal immigrants seeking sanctuary, most of whom are shipped off to horrifying refugee camps. Theo (Clive Owen) is a government bureaucrat who is kidnapped by a group of activists, one of whom proves to be his ex-wife (Julianne Moore).

She wants Theo to help them snag travel papers so they can escort a young refugee named Kee out of the country. He soon learns why Kee is so important: she’s pregnant.

Theo spends the rest of the movie trying to get Kee to the coast, where she will theoretically rendezvous with “the Human Project,” a mysterious scientific group allegedly working to cure global infertility.

Along the way, Kee gives birth to a baby boy. After crafting a thoroughly dreary and depressing world, Children of Men ends on a note of bittersweet hope as Theo dies of his wounds just as The Human Project’s vessel emerges out of the fog to rescue Kee and her child.

But in the book: The movie touches on the celebrity status granted to the last generation of humans, but the book delves into more detail about these “Omegas,” who get doted on and raised in luxury.

The result is a group of violent, spoiled little snots who have nothing but disdain for their elders. Government has become largely totalitarian, where juries have been abandoned, and conviction means banishment to a penal colony without hope of parole or pardon.

Foreign Omegas are imported for labor purposes and then booted out of the country when they reach the age of 60.

The novel is partly told as the diary of Theo, who in the book is an Oxford don rather than a government cog. He’s cousin to Xan Lyppiatt, the self-appointed “Warden of England” whose despotic reign is largely unopposed as the populace has lost interest in politics in light of the imminent end of the species.

There are still people aligned against the Warden, however, including the “Five Fishes,” a group that approaches Theo and asks him to carry their requests for various reforms to Xan. He does so, but Xan correctly guesses that they didn’t originate from Theo, and becomes determined to track down the dissidents.

Theo goes on the run with the Five Fishes, eventually learning that one of them is pregnant with the first child conceived in decades. The Fishes are betrayed by one of their own, the baby is delivered, and Theo eventually shoots and kills Xan, with the book suggesting that Theo will be the next ruler of the country.

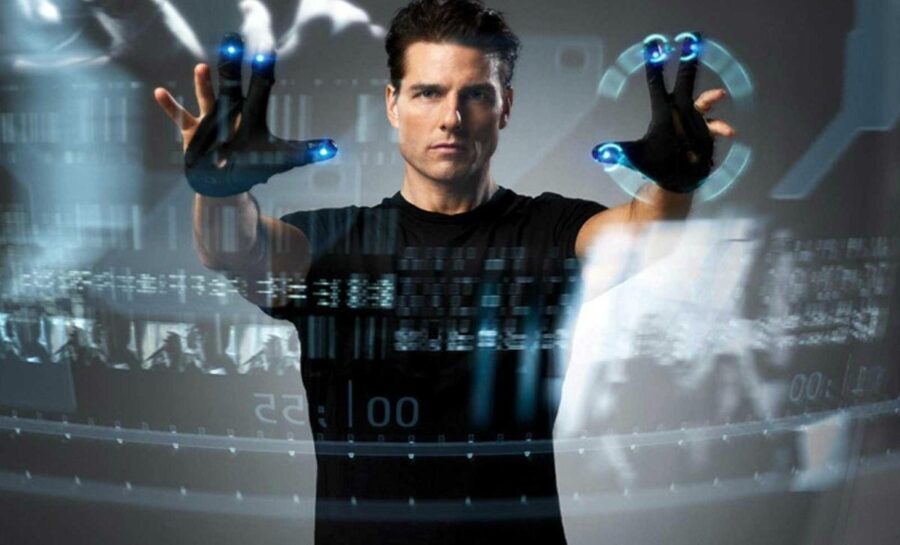

Minority Report

Source material: Philip K. Dick’s “The Minority Report” (1956)

In the movie: In 2054, Captain John Anderton (Tom Cruise) is head of Washington D.C.’s controversial “PreCrime” unit, which acts to prevent murders before they happen, all based on the visions of three mutant “precogs.”

PreCrime is on the cusp of going nationwide when Anderton faces the unthinkable: a prediction that, in 36 hours, he will murder a man he doesn’t yet know. Anderton kidnaps one of the precogs (Samantha Morton) and goes on the run, hoping somehow to prove his innocence.

Anderton eventually learns about the existence of “minority reports” — when one of the precog’s visions doesn’t line up with the others. These are usually discarded, but Anderton soon discovers that someone has used this PreCrime loophole to commit the perfect murder, one that will be dismissed as a minority report.

After Anderton pursues the man responsible, it is proven that foreknowledge of your future can allow you to change it. As a result PreCrime is discredited and shut down.

But in the book: As in the film, Dick’s original story is essentially a dissection of free will versus predestination/determinism.

Rather than being in its infancy, PreCrime in the book is three decades into its existence. It also isn’t limited to handling murder cases, so presumably you could get a ticket for littering before you even bought the soda can you were eventually going to throw out your car window.

The book states that “Precrime has cut down felonies by 99.8%.” That’s even better than Judge Dredd’s clearance rate.

Instead of Washington D.C., the book’s story unfolds in New York City. Like many movie adaptations of Dick’s work, the protagonist doesn’t share the movie-star good looks of its lead actor.

Instead, Anderton is in his 50s, balding, and out of shape. Even more importantly, he’s actually the creator of PreCrime. As in the film, Anderton finds himself on the pointy end of the system he’d served, with the precogs predicting that Anderton will commit a murder.

In the book, however, his victim is a military general who is determined to discredit PreCrime. How that prediction plays out, however, is hugely different. In the book, Anderton actually does kill his predicted target in order to preserve PreCrime. So, it’s pretty much the exact opposite of how the movie plays out.

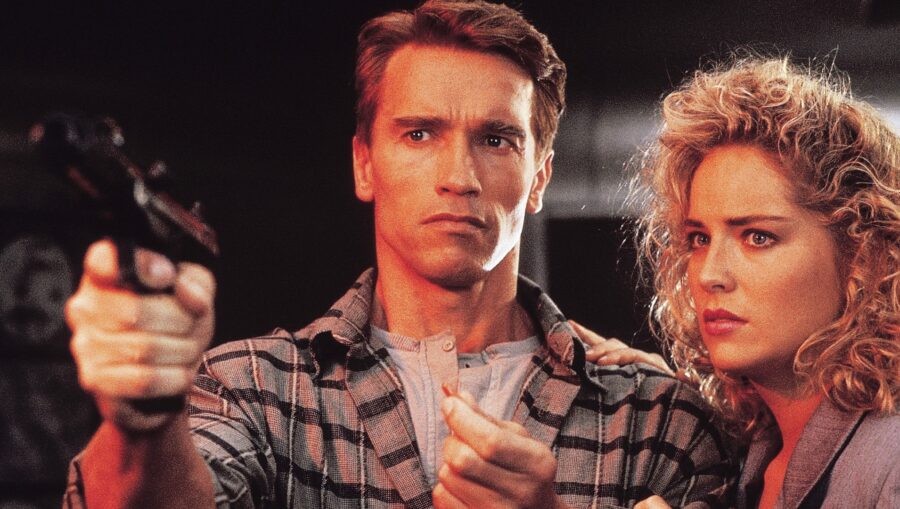

Total Recall

Source Material: Philip K. Dick’s “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” (1966)

In the movie: Inexplicably-ripped construction worker Douglas Quaid dreams — both literally and figuratively — about Mars. Against the advice of his buddy, he visits Rekall, where he purchases implants that will give him all the memories of his ideal Mars vacation.

Unfortunately, the process reveals that Quaid’s simple life was a lie: he’s a former secret agent whose memory had been wiped, and his wife is just another agent tasked with making sure he doesn’t remember who he truly is.

He makes his way to Mars, where he hooks up with the resistance against the ruthless Martian governor Vilos Cohaagen and discovers his mind holds the secrets to an ancient Martian machine that could reshape the red planet.

Or, just possibly, he never woke up at Rekall and everything is unfolding in his head while he’s a vegetable in the real world.

But in the book: Douglas Quail is no musclebound he-man, but rather just an average joe who works as a clerk. Like Quaid, Quail fantasizes about a Mars vacation, so he visits REKAL to get an “extra-factual memory” of an adventure on Mars as a spy.

As in the film, the REKAL workers freak out when they uncover his real memories, so they erase the memory of his REKAL visit and send him home. Soon enough, however, a pair of cops show up and try to murder Quail.

See, he’s got a device in his noggin that allows his former bosses to read his thoughts, and they don’t want his memories coming back.

And here’s where Paul Verhoeven’s film and Dick’s story part ways. Quail never visits Mars, there’s no twist about him being a double agent, and there’s no ancient alien technology for him to unlock.

Instead of going on the run, Quail cuts a deal where REKAL will re-erase the memories of his Mars mission, as well as tweaking his brain in such a way that he’ll never have any desire to return to REKAL. But here’s where things get weird: his new memories, rather than just returning to him the boring life he thought he had, convince him that aliens visited him as a child, and that his continuing survival is the only thing standing between mankind and an extraterrestrial invasion.

But, just as happened before, as they are preparing to implant the fake memories, it is suggested that those memories are real too. Which, yeah, is a bit out of nowhere compared to the film’s more elegantly ambiguous ending.