Sci-Fi Master Robert A. Heinlein Wrote A Book About An Evil Wakanda, And Some People Think It’s Racist

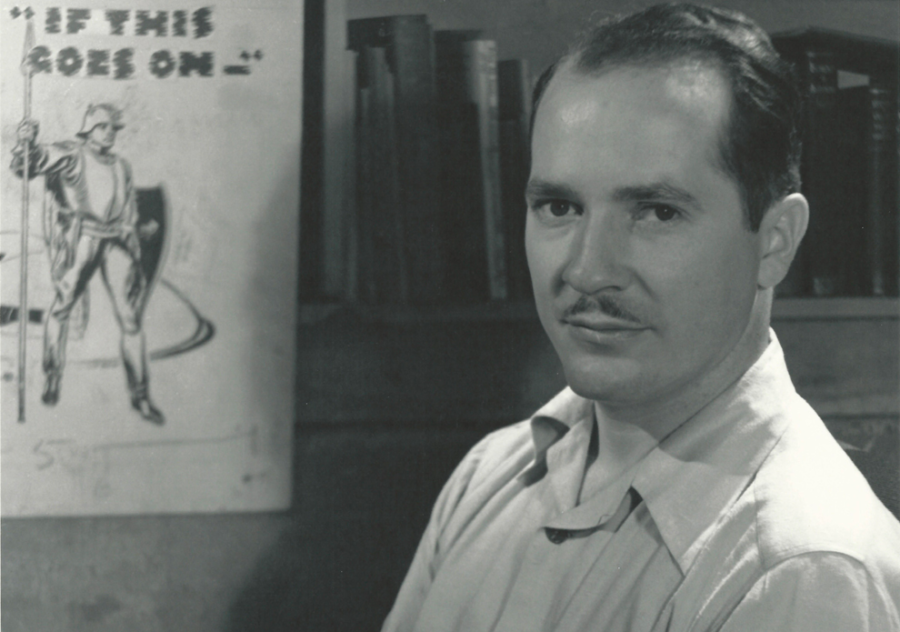

Robert A. Heinlein is, without question, one of the greatest science fiction writers of all time. That’s especially evident when you look at his earlier work.

Old age did not do well by Heinlein, and as he got older, his biting, pointed writing became bitter, and the sexual freedom he espoused in his work turned into something more like the mad ravings of a crazy old man who was clearly, despite his age, still very very horny. Even that, though, still had its moments.

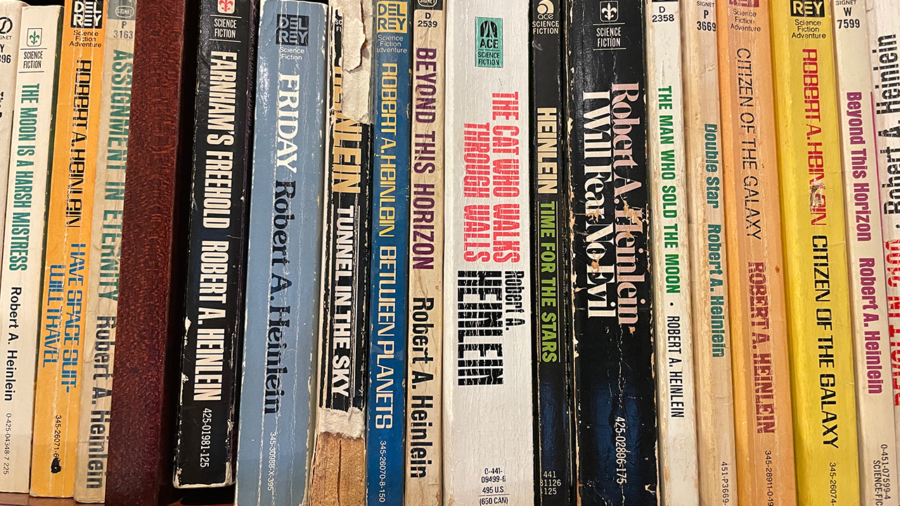

His early and mid-career work is regarded as genius, and he’s one of the original fathers of meaningful, modern science fiction. He’s also written a lot of books, forty-plus years of material.

Not all of his books have aged well, though. In particular, activists have a problem with Farnham’s Freehold.

So what is all the controversy about? The book takes place in a dystopian world where people with dark skin are the most technologically advanced and the most powerful people on the planet. In a sense, it’s even a little like Wakanda… if the Wakandans were evil slave owners.

Critics argue that Heinlein’s portrayal of the dominant black culture in the novel reinforces negative stereotypes about African-descended people, depicting them as cruel and barbaric. Was that his intention? Or was it his intention to portray African-descended people as super smart, advanced, and the most successful? That’s where the questions start.

In the future of Farnham’s Freehold, technologically advanced African-descended people have enslaved whites. This has been interpreted by some as a reactionary fantasy, reinforcing the fear of a reversal of racial power structures. This aspect of the novel has been criticized for its potential to perpetuate white supremacist fears.

It seems somewhat unlikely that this was Heinlein’s intention. Supporters of his writing argue that he was attempting a satirical critique of people’s views of racial power dynamics. Heinlein himself never spoke on the controversy. He died in 1988, and back then, no one interpreted the book as it is currently interpreted by modern cancel culture. Until and for years after Heinlein’s death, Farnham’s Freehold was viewed as a satirical critique of racism intended to challenge the reader’s assumptions about race and power.

Given the nature of his other work, it’s hard to imagine Heinlein actually set out to write some sort of crazy racist narrative. His other books were symbols of the free-love hippie movement, which challenged cultural norms back in the days before it was acceptable to challenge them. His entire ethos, in everything else he wrote, is built around total personal freedom and total equality for everyone. Those ideas were pretty radical at the time. Some of them still are.

On the level of the quality of Heinlein’s writing, at least, Farnham’s Freehold was one of his better efforts. The book begins with a Cold War-era tale of a family hiding inside a home-constructed bomb shelter when the doomsday clock strikes midnight and nuclear war lands right on top of them.

The interesting thing about Heinlein’s writing, perhaps here more than in anything else he’s ever done, is how he manages to convey a vivid picture of what’s happening without bothering with actual visual descriptions of the environment in which he thrusts his characters.

Rather than describing the way his world looks, Heinlein chooses instead to describe the way his characters react to it, and through them, his readers not only get the picture but sometimes a deeper understanding than you’d get had he described simple surface knowledge.

In Farnham’s Freehold, the book’s most mind-blowing moment happens early on, as Heinlein’s male and female lead huddle inside their homemade bomb shelter, the floor shaking and the world above them exploding, and with nothing but death awaiting them they engage in a kiss, which leads to hinted at sex.

Heinlein is often sexual in his writing, but the book was written in 1964, and anything more than a makeout session in mid-explosion probably would have been deemed pornography by the era’s censors.

What’s amazing about it is the way he threads their fear, terror, passion, lust, and all of their emotions at that moment into the fabric of his story to make their horrible, terrifying situation come vibrantly alive. For that moment, you’re there in that bunker with them, with the world ending all around you, in a place where none of the things you used to care about matter since, at best, you’ll be dead in a few hours.

Of course, the entire book doesn’t take place in a bomb shelter, and if you’ve read the dust jacket on it, then you know that the nuclear explosions above somehow slam their little shelter forward in time to a future where white people live in slavery, and everything we’ve ever known is buried under thousands of years of dust. The book never works quite as well once Farnham and his little group are forced to interact with that future, but for the controversy-free first half, when they’re alone and trying to eke out an existence, the novel soars.

Farnham’s Freehold is worth reading for that first half alone. The rest is, perhaps, worth reading too, if only to decide for yourself if stoking the fears of white supremacists is what Robert A. Heinlein actually intended.