Oppenheimer Needs To Teach One Lesson About Movies That Must Change

When Oppenheimer and Barbie rolled into theaters, conquering box offices and winning accolades from critics, many proclaimed that, at long last, the movies were back. Perhaps without realizing it, what they really meant was that original films, made for adults, starring big names, and benefiting from compelling writing and directing were back. As in, less Marvel and more Nolan: the return of original content serving audiences narratives they’re largely unfamiliar with.

Oppenheimer As Original

This risk—introducing somewhat unfamiliar content—didn’t used to seem like a risk. People went to see The Exorcist or Chinatown without reading The Exorcist comic or playing the Chinatown video game because neither existed. Instead, the films sported unencountered plots, engaging screenplays, and beloved household name stars.

That latter factor is subtle but significant for Oppenheimer as much as any film. After all, it’s an emergent cliche of today’s Marvel-saturated Hollywood that “the star doesn’t matter.”

People line up to see Batman, the conventional wisdom proclaims, not Christian Bale or Robert Pattinson, yada yada.

However veritable, this maxim underscores the dilution of star power.

Still Need Star Power

But star power was fun; star power, combined with new narratives and potent directing, engendered the valuable, rich movie-going experiences we used to regularly enjoy.

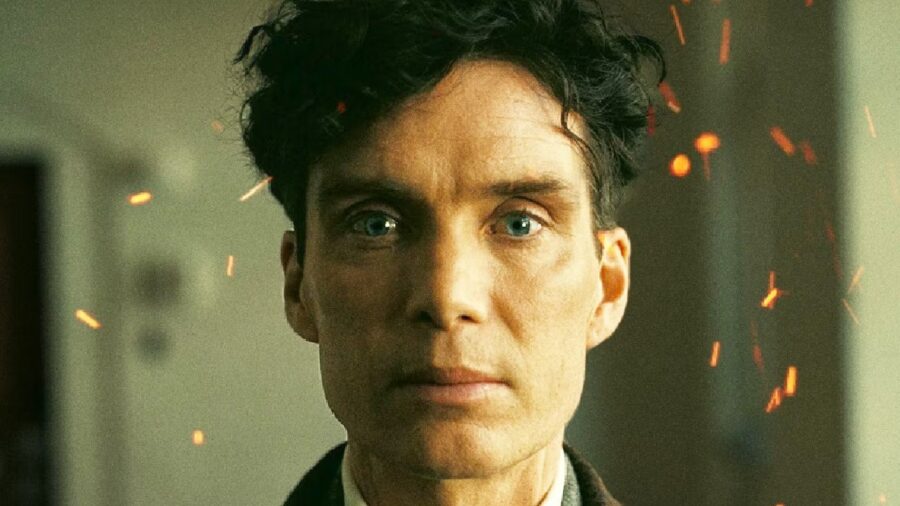

For Oppenheimer, Cillian Murphy mattered as much as Christopher Nolan. If the film lacked a household name leading actor or an auteur director, the results would have been vastly different, and inferior.

For example, Julia Roberts largely enticed people into theaters for Erin Brockovich—the actor, her face, and brand. Then, Susannah Grant’s fantastic screenplay, based on Erin Brockovich’s amazing true story, joined forces with Steven Soderbergh’s direction to achieve greatness.

Becoming The Norm Again?

The effect of such a formula—Oscar wins, rave reviews, box-office bounty, word-of-mouth appeal, cultural impact, repeat viewings, etc.—can become the norm again.

After all, people designed, printed, and sold “Barbiehammer” (Oppenheimer combined with Barbie, for those living under rocks) t-shirts themselves; they wore them to theatres voluntarily.

Why? Because audiences are sincerely starved for original movies directed by actual artists, written by legitimate writers, and starring the kind of actors that inspire fanbases.

The understandable derision of Madam Web—the gargantuan fatigue surrounding yet another superhero flick, another soft reboot (White Men Can’t Jump with Jack Harlow? Ugh)—is the flip side of this same coin.

Meeting Hollywood Halfway

And, no, new films enlivened by originality need not be utterly, inflexibly original. Oppenheimer, of course, was largely based on the non-fiction book American Prometheus. In other words, we’re open to meeting Hollywood halfway.

Take The Last of Us, for example; it’s based on a video game. But the game is superb, a classic of the medium because of its incredible narrative, not despite it. That’s why HBO adapted it in the first place: to shape new content bouyed by strong, but not yet world-famous (as in, your parents haven’t heard of it) source material.

Successful Approach

Not only was Oppenheimer’s approach successful, but it was also the winning approach of the 1960s and 1970s Hollywood New Wave, whhich brought us perhaps the most compelling films in cinematic history.

Jaws, for instance, was based on a successful novel. Jaws virtually defined what a blockbuster can be.

The list of films sharing this approach from the same era is staggeringly long: The Godfather, A Clokwork Orange, Midnight Cowboy, 2001: A Space Odyssey. And these are merely films based, however minimally, on fiction source material. Plenty from that era were totally original, but the technical originality wasn’t the point.

Vision And Commitment To Art

Like what Christopher Nolan did with the actual J. Robert Oppneheimer’s biography, what Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, Robert Altman, and company did with their narrative templates was what counted. The directorial vision—the inspiration, the commitment to art—was what won global attention and affection.

Likewise, the screenwriting prowess of Dan O’Bannon’s handling of Alien (subtle, horror-forward, “realism” inspired sci-fi) or Terrence Mallick’s screenplay for Badlands (an off-kilter, intelligent, disturbing take on romance) explained much of their success.

This is what Oppenheimer did right, and this is why it matters. If Hollywood wants to matter again, it should take note.