Nosferatu Only Exists Thanks To Criminals

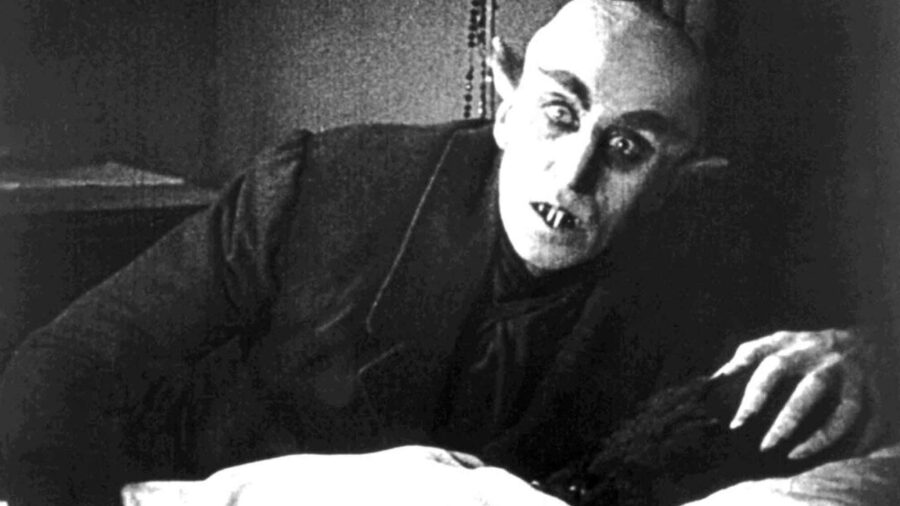

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) just might be the first real horror movie. It’s one thing to look at Bella Lugosi in Dracula (1931) and think, “That’s scary? Okay boomer…” But Nosferatu‘s bald, rat-toothed Count Orlok with his long, spindly fingers is legitimately creepy, even in 2024. It’s no exaggeration to say that Nosferatu is an essential milestone in horror filmmaking. Thank god someone was smart enough to steal it.

Is It Stealing If You Just Don’t Know?

Steal it, conceal it, and smuggle it abroad—Nosferatu owes its very survival to criminal behavior. Fitting since the film’s production was arguably illegal from the get-go.

Copyright law wasn’t as well established in 1922 as it is now. So it’s entirely conceivable that when Nosferatu director F.W. Murnau set out to adapt Bram Stoker’s Dracula without permission, he didn’t quite realize he was committing a crime.

On the other hand, the German director did go through the trouble of changing some aspects of the book, calling into question his ignorance of the subject.

Yes, Apparently It Is

Regardless, word of this unofficial adaptation reached Stoker’s widow, and that’s when the proverbial sh*t hit the fan. Florence Stoker became aware of Nosferatu when she received a copy of the program for the movie’s Berlin premiere.

The program allegedly stated point blank that the film was based on Dracula, something Florence found peculiar since she didn’t remember selling Murnau the rights.

Now, Florence Stoker was not some kind of money-hungry golddigger who valued commerce over art. She was a widow in an era when women weren’t allowed to work and, as a result, depended entirely on her late husband’s royalties for survival.

From her point of view, Nosferatu was making money off the Stoker name, and she deserved her fair share.

Destroy It All

Meanwhile, Prana, the company responsible for producing Nosferatu, went bankrupt before the movie could do much business. Stoker took them to court anyway, and after a three-year legal battle, she realized she wasn’t going to get any money from Prana.

So she settled for destroying every copy of Nosferatu in existence instead.

Not personally, of course. Florence requested that all copies and negatives of Nosferatu be rounded up and obliterated.

The German court agreed, and that’s what happened. Or at least it was supposed to.

Noncompliance

To this day, no one knows who precisely defied the court order. All we know is that a handful of people refused to hand in their prints or otherwise rescued copies of Nosferatu from certain death.

That shocking display of noncompliance is the only reason Nosferatu exists today. Period.

Unfortunately, this is also why Nosferatu has more in common with Frankenstein these days than Dracula.

Over the years, these “illegal” prints weren’t given the care they deserved. As a result, no single complete copy of Nosferatu exists today.

It’s The Differences That Made It Great

Every version of Nosferatu you’ve seen has been painstakingly composited from multiple sources—in some cases, frame by frame. That means it’s been over a century since anyone saw Nosferatu in its intended form. Sadly, unless we invent time travel, no one ever will.

Ironically, Murnau’s changes to distinguish Nosferatu from Dracula are what made it such a great film. Count Orlok’s horrific appearance and unique death contributed to the vampire mythos.

Orlok is the first vampire ever killed by sunlight, a trope now synonymous with the undead. Meanwhile, actor Max Schreck’s makeup made the vampire a creature of terror rather than one of seduction.

All in all the horror genre and cinema in general would look very different if Florence Stoker had gotten her wish. Luckily, a few daring souls decided to break the law, and Nosferatu is still scaring audiences all these years later.