Why Star Trek: Enterprise Failed

The 1990s were a time unlike any other for science fiction. That was especially true for Star Trek.

Four movies, two of them big hits. Four-hundred and thirty-six television episodes spread across three different shows, all of which completed full seven-season runs while earning both fan and critical acclaim. Star Trek has never been more significant than it was in the 90s.

However, as the decade drew to a close, there were signs that Trek’s best days might be behind it. Star Trek: Voyager’s ratings faded in its final seasons, and the last 90s Star Trek movie, Insurrection, underperformed at the box office.

In 2001, the powers that be made a big move to remedy that slight downturn in interest by taking Gene Roddenberry’s vision in a fresh direction. For the first time, Star Trek would stop moving forward. The franchise was winding the clock back to where the Federation began.

Their plan was to rediscover the spirit of adventure and exploration that used to be the hallmark of what had now become an aging franchise increasingly overloaded with complex rules and techno-babble.

So, when Enterprise debuted on UPN in 2001, it was with a sense of self-assured success. They were wrong. The show was canceled after only four seasons.

This is why Star Trek: Enterprise failed.

How Rick Berman And Brannon Braga Created Enterprise

Rick Berman and Brannon Braga were the minds in charge of Star Trek throughout the 80s and 90s. Their leadership and their ideas helped transform Gene Roddenberry’s canceled TV show into a multimedia empire. So it makes sense they’d be confident in what they were doing.

Berman and Braga were so certain this new plan would work that, at least not until it became clear in the third season that it wouldn’t, Enterprise didn’t bother to put the words “Star Trek” in its title. An audience would find it, support it, and love it no matter what they called it. Or so they thought. They may not have been wrong.

Had Enterprise turned out to be any of the things it was supposed to be, all of those suppositions might have come true. We know this because five years after its cancellation, director JJ Abrams pulled off all the things Enterprise initially promised, albeit in a much dumber, lens flair-coated package, with his 2009 Star Trek prequel movie. It was a huge hit.

Prequels are a groan-worthy cliche now, but they weren’t a dried-up husk of anti-creativity yet, in the year 2000.

Enterprise Becomes A Series At War With Itself

Enterprise was supposed to take us back to the beginning of the Federation, before the time of Captain Kirk and Spock, to the first starship to bear that famous name, in a tumultuous galaxy humans were only beginning to understand.

More importantly, Enterprise was meant to be different in style and tone. Berman and Braga wanted a stripped-down approach, one that emphasized human determination over excessive reliance on technology. The show’s excellent production design reflected that.

Its scripts were less consistent. Rather than fully embracing this low-tech premise, Enterprise became a television series at war with itself.

The show’s pilot, “Broken Bow,” immediately centered the series around time travel, setting in motion events that would waste what should have been an interesting start on a half-hearted season-long temporal cold war that went nowhere. Worse, by making time travel the show’s primary focus for season one, they sidelines much of the era they’d worked so hard to set things in, telling stories that could have been told in any place at any when. That was only the first of the show’s missteps.

Though Enterprise was meant to be a fresh start, it repeated many of the problems that had caused Voyager’s ratings to sag. Among those unforced errors was Enterprise repeating Voyager’s excessive reliance on meaningless technobabble. It felt even more out of place on a show specifically designed with simplicity in mind.

The Infamous Theme-Song

Like the series itself, the Enterprise opening credits were meant to signify something fresh, embodying the spirit of excitement and adventure that the show’s creative team hoped to recapture. Casting off the traditional ship-flyby open used by all previous Star Trek incarnations, Enterprise created a visual history lesson that rocketed through the accomplishments of human exploration.

Then it ruined that otherwise exciting montage by setting it to an awkward song about faith crooned by a Rod Stewart knockoff. Nothing says exploration and adventure quite like Christian Elevator Rock.

Later, when Rick Berman’s team realized everyone hated the song, they tried to fix it by speeding up the tempo. Like setting a Michael Bolton song to a Bossanova beat cranked out of a Casio, this made something bad worse.

Enterprise Is A Great Star Trek Show

This analysis may make Enterprise seem terrible, but it isn’t. When considered in total, Enterprise is a very good Star Trek show, better even than its direct predecessor, Star Trek: Voyager.

Enterprise excels at all the little things. For example, the crew’s fear of using the newly invented transporter system is an ongoing subplot in every episode. The show sticks with it, keeping the team running around in shuttles and coordinating docking sequences.

A lesser series would have been unable to resist overusing the ship’s transporter to save both time and money on production. Enterprise resists that temptation, so this small decision, and many others like it, adds a feeling of danger and instability to everything the series does.

Captain Archer: Patron Saint Of Missed Opportunities

The show is a constant push and pull between those good ideas and other missed opportunities. Nothing in Enterprise embodies that better than its series lead, Captain Archer, as played by veteran sci-fi actor Scott Bakula.

Bakula was already a big star when he joined Star Trek, thanks to the acclaimed time travel series Quantum Leap. Bakula’s Quantum Leap character was built around a sort of old-fashioned, well-meaning, aw-shucks naïveté. He brought all of that with him to play Captain Archer.

The unusual thing about Archer is that he’s not very good at his job, and he shouldn’t be. He’s the first. He went out exploring without any rules, directives, or red alert protocols and expected everyone he met to give him a friendly smile and an extended hand. Aw shucks Bakula is perfect for that.

Starfleet had no idea what it was doing when it picked its first Captain. In Jonathan Archer, they picked wrong. The Archer Enterprise introduces us to is careless and sloppy. He’s too trusting, too eager, too damn friendly. It’s constantly getting his ship in trouble.

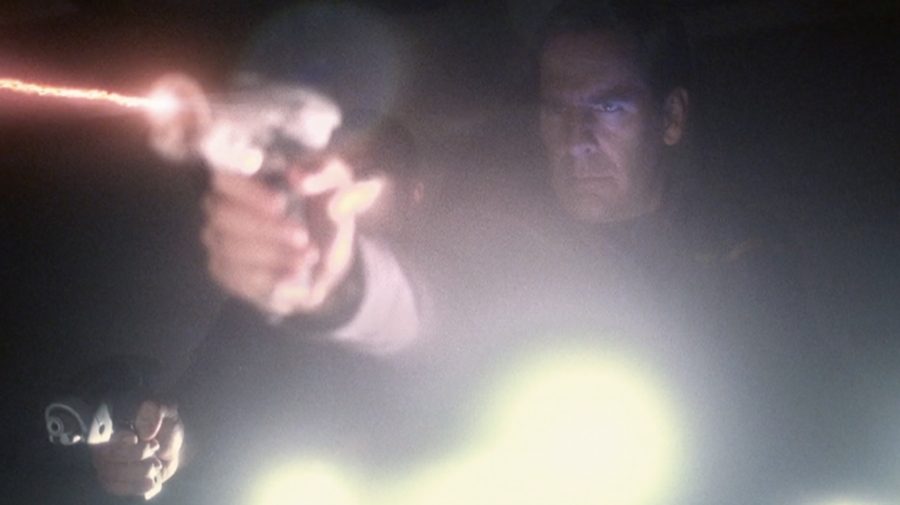

When things don’t go as planned, Archer pouts and complains that aliens are mean. As the missions get tougher, he becomes increasingly unhappy, miserable, and even morose. His friendly demeanor is replaced by a scowl. He begins holding grudges, shooting first, and asking questions later as the seasons wear on.

This may sound like criticism, but I mean it as praise. Archer’s ability to make the best of a bad situation he’s not at al suited for is the most interesting thing about the show. Rather than fully exploring it, Enterprise resorts to telling us how great he is with verbal diarrhea and doe-eyed reactions from his crew, rather than grappling with long-term consequences.

As the show’s writers became increasingly out of touch with the character, Archer turns into a placeholder for an already determined future success. His attitude doesn’t matter, his mistakes don’t cost them anything, and his decisions are rendered irrelevant as Enterprise gives him a pre-determined, grand destiny.

An ill-equipped Archer struggling to figure out how to command on the frontier should have been the entire show. Instead, they kept trying to narratively force the character into Captain Kirk’s cookie-cutter mold while Scott Bakula gave us something else.

Archer isn’t Captain Kirk. He’s obsessed with water polo. He spends his off-duty hours hugging a Beagle. He’s more comfortable talking about warp theory than negotiating with hostile aliens or making out with green women.

Enterprise never fully embraces who Archer is. He has a destiny, and one way or another, he has to fulfill it.

Putting T’Pol In Charge Causes Problems

The rest of the ship’s crew are a similar mix of good ideas that never fully come to fruition. That’s especially true of T’Pol, who, in her most vital moments, serves as a reality check for Archer, the person to tell him he has no idea what he’s doing.

It wasn’t a bad idea to have a Vulcan on Enterprise. After all, this is a Star Trek set in the very earliest days of humanity’s awakening. Vulcans are the first aliens encountered by humans and would, logically, be one of the few alien races they’d be well acquainted with during this period.

It was, however, a bad idea to make that Vulcan Archer’s first officer. T’Pol could have served that same function as a science officer or observer outside the human command chain.

Enterprise is supposed to be a show about mankind’s first leap out into the stars. Instead, it’s a show about humans reaching out into the stars whenever Archer’s on the bridge. When he’s not, it turns into a show about how a Vulcan named T’Pol told humans what to do on their first attempt to go it alone.

It’s particularly wrong-headed in light of Archer’s own resentment towards Vulcans. He sets out on his journey, determined to prove humans don’t need help from Vulcans. For his initial act as Captain of Earth’s first warp 5 ship, he makes a Vulcan his first officer. Nothing about this makes sense.

It makes less sense when you consider what Enterprise made out of the Vulcans. Missing were the logical, peace-loving aliens we’ve grown to know and love as part of the Trek universe. In their place were a bunch of angry, pointy-eared, close-minded racists with an addiction to spray tan and a penchant for murder and threats.

In the show’s final season, there was a last-minute, half-hearted attempt to reconcile all of this and turn the Vulcans back into creatures best known for their inability to lie, but by then, it was too little, too late.

The frustrating thing here is that T’Pol is a good character, and Jolene Blalock is good at playing her. It must also be said that Berman and Braga mostly hired the incredibly beautiful and petite Jolene to be photographed in her underwear, something the show often does.

To be fair, the Enterprise also gives male crewmembers similar lascivious attention. Trip Tucker often ends up shirtless and entwined in uncomfortable sexual situations. It gets so wild that at one point, he ends up pregnant.

So, unless you’re a total puritan, there’s nothing wrong with seeing T’Pol in her Vulcan underwear now and again if, outside of that, the show gives us other things to build up her character. But it never did enough, and Blalock isn’t able to elevate the scripts they give her, as Jeri Ryan did on Voyager.

An Emotionally Volatile Engineer

Charles “Trip” Tucker III, played by Connor Trinneer, is the ship’s catfish-lovin’ Southern engineer. He’s also emotionally unstable and a constant source of problems for his Captain.

In one of the best gags on the animated series Star Trek: Lower Decks, an alternate universe version of T’Pol appears who, after marrying Trip Tucker, uses her experience interacting with him to become a top expert on human emotions.

Somehow this walking emotional time bomb is third in command of the ship. Given his behavior, this rank never made much sense.

The Enterprise creative team writes Trip like a wet, behind-the-ears Ensign, not a reliable, seasoned officer. Luckily, Trineer’s performance is so much fun he’s easy to love.

Phlox Is Better Than Catching Bats

Phlox, the ship’s Denobulan doctor, may be the most consistently interesting thing about Enterprise.

The character comes off as an extreme optimist, but in interviews, actor John Billingsly claims Phlox may actually be the opposite. He’s playing him as if Phlox is so resigned to his fate that he’s totally unaffected and unconcerned. By being so accepting of any outcome, no matter how bad it might be, he’s unbothered and carefree.

Dozens of episodes could have been written about Phlox’s complex marital arrangements, but of course, they weren’t.

Enterprise Underserves Its Guest Stars

Enterprise scored great guest stars. Some it wasted. A guest appearance by Scott Bakula’s Quantum Leap companion, Dean Stockwell, was squandered on a generic character unworthy of his talents.

Jeffrey Combs’ brilliant performance as the Andorian Commander Shran demanded he be used as a recurring character. He was, and every time he shows up Enterprise reaches a new level.

His brilliance should have also prompted them to go a step further and find a way to make Shran part of the regular cast. There were rumors that this might have been the plan if the show had gotten a fifth season, but it did not.

Enterprise Didn’t Move Fast Enough To Save Itself

There’s so much more that could be said about what Enterprise got right. The rest of the supporting cast works nearly as well as the ones we’ve highlighted. Malcolm Reed’s obsession with protocols. Hoshi’s fear of, well, everything. Mayweather’s past growing up on a space-faring freighter.

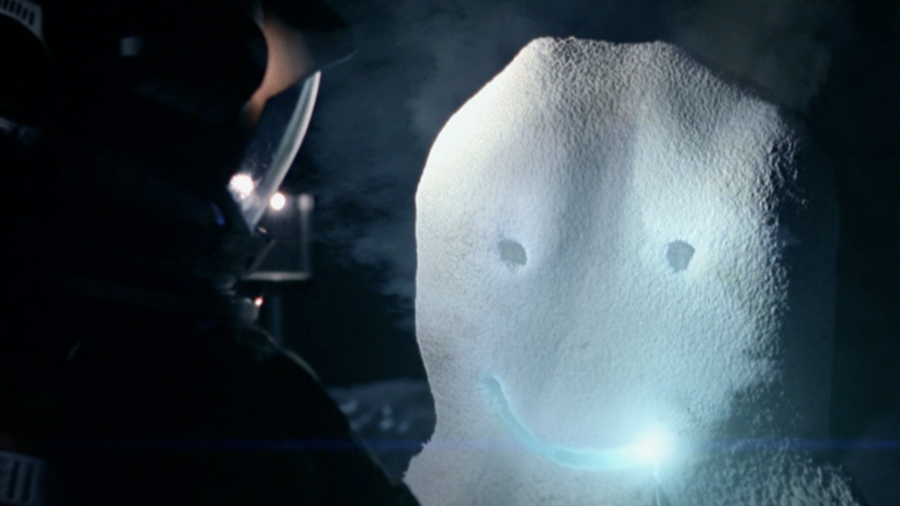

However, Enterprise never moved fast enough to capitalize on its strengths. Shran got a couple of episodes a season, and Phlox was kept locked away in his sickbay chasing the occasional escaped Tyberian bat.

With cancellation imminent, in the latter half of its fourth season, Enterprise tried to become the show it should have been all along. That effort resulted in a flurry of episodes involving the alien races Archer and his crew were meant to befriend in order to pave the way to the Federation we knew from Kirk’s Trek-era.

The stories they should have been telling were condensed into a few episodes and shoved out the door at warp speed, a last-ditch effort to get the Enterprise where it was going before the axe fell.

It was too late. Nothing they did would matter. In 2005, after four seasons of sinking ratings, Enterprise, by then retitled Star Trek: Enterprise, was canceled.

Why Enterprise Was Canceled After Only Four Seasons

Enterprise was supposed to be a grand new vision focused on exploration and adventure, a show about the triumph of the human spirit. Instead, it kept getting bogged down in worn-out gimmicks, like time travel, that it never needed.

Those problems would have been solved with time. Enterprise was warping in the right direction when it was canceled. Most good shows take a few seasons to find their sea legs, and Enterprise had found its equilibrium when Paramount gave up on it.

Enterprise’s producers built their show around the idea of faith, but their work caused Hollywood to lose faith in the entire franchise, sending longtime steward Rick Berman to the unemployment line and Star Trek into the high-octane style over substance hands of Alex Kurtzman and JJ Abrams.

Enterprise wasn’t perfect, but it was good—maybe even great. I love it more with every passing year. But its failure killed Gene Roddenberry’s dream, and given the horrors Kurtzman has beamed into Star Trek since, Enterprise’s failure may have killed that dream forever.

Enterprise should have been Star Trek’s future. Now it’s the last, best gasp of the greatest sci-fi franchise’s golden era.