Demolition Man: Critics Hated It But Now Stallone’s Movie Deserves Better

Demolition Man foresaw the coming wave of wistful societal longing for an earlier time that struck land roughly a decade later.

This article is more than 2 years old

To describe Demolition Man as overlooked isn’t entirely accurate. When the Sylvester Stallone/Wesley Snipes sci-fi action movie opened in 1993, it debuted at number one at the box office and eventually took in $159 million worldwide. While that doesn’t sound super impressive by today’s metrics, in the ‘90s, standards were different and while not world-shattering, it was still a decent haul.

That said, while maybe not popularly overlooked at the time, and it certainly has defenders now, Demolition Man often serves as the butt of a lot of jokes. Especially those concerning the ironically iconic “three sea shells” that replace toilet paper in the future. In general, critics panned the film, and though it has some staying power in the public consciousness, it’s often remembered with a tone of scorn—people love to mock Snipes’ bleach-blond hair, the sea shells, the fact that Taco Bell was the only restaurant to survive the “Franchise Wars.”

Demolition Man begins in the not-so-distant future of 1996, where the world has descended into a chaotic firestorm of unchecked crime. It’s kind of one last gasp of the ‘80s, we’re-on-the-brink-of-social-collapse narrative that was so popular in the media and in politics at the time. (Crime in America was actually in a sharp decline in this era, despite that widespread perception.)

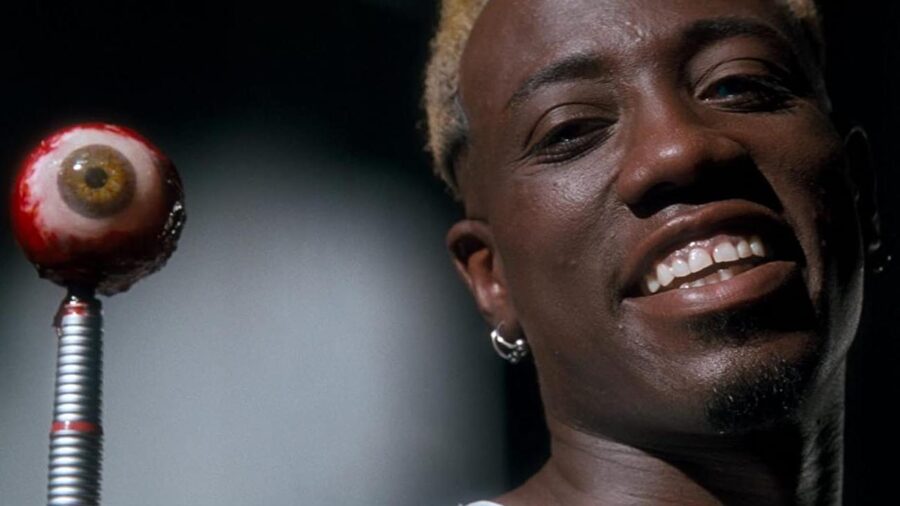

John Spartan (Sylvester Stallone) is a no-holds-barred cop who always gets his man, no matter what he has to destroy in the process. Hence the nickname, Demolition Man. When super-criminal Simon Phoenix (pre-tax-evasion Wesley Snipes, who served as the inspiration for Dennis Rodman’s later career aesthetic) kidnaps a bus load of hostages, only one man is brave enough to venture into a criminal no-man’s-land. Phoenix kills the hostages, but frames their deaths as the result of Spartan’s reckless action and both men end up in “cryo-prison.” Ice cubes sitting in jail.

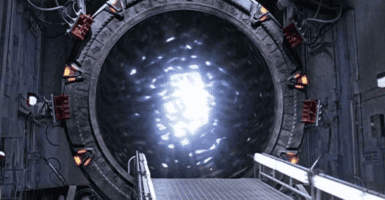

Fast-forward to 2032. Society, finally pushed past the point of no-return by crime and disease, collapsed and was rebuilt as a peaceful, crime-free utopia where everyone wears long flowing robes, is nice to each other, and gets fined for swearing. It’s an extrapolation on the early-1990s fear of what political correctness might lead to and that freedom means being able to do whatever you want, whenever you want, regardless of the impact it has on anyone or anything else. So, there’s no sex, no profanity, and really no fun—especially according to antisocial rebel, Edgar Friendly (Dennis Leary at the height of his Dennis Leary-ness), who just wants to eat a cheeseburger, jerk off, and be offensive any way he sees fit.

Into this peaceful tedium, Simon Phoenix escapes, effecting the first non-natural deaths—Murder, Death, Kills—in decades. Since the current police force is helpless to stop any sort of actual criminal, they thaw out the man who caught Phoenix in the first place. As one may imagine, society is not prepared for the onslaught of violence and depravity unleashed upon it.

Yes, Demolition Man certainly is goofy and campy. Yes, everyone sings along to ‘50s jingles as popular songs. And yes, it falls prey to that fate that so often befalls movies attempting to predict a future: viewers love to look back at the futuristic movies of the past and say, with smug satisfaction, “Well, that didn’t happen.” But to dismiss the film is as nothing more is to ignore a couple of key things.

First, Demolition Man is super damn fun. The debut feature of Marco Brambilla—and to be honest, the highlight of his directorial career—the action is solid, fitting in nicely with this ear of Stallone’s career, especially when the Rambo star faces off directly with Snipes.

Speaking of Snipes, he has an absolute blast goofing on this new world, pummeling unsuspecting future dwellers, and chewing every last bit of scenery he can find. He plays Simon Phoenix a bit like an over-the-top comic book villain, in the vein of Jack Nicholson’s Joker on speed.

The social satire doesn’t always find its mark, but when it does, it’s sharp, thanks in large part to uncredited rewrites from Fred Dekker. And while the proposed future is a ludicrous faux-utopia, it does, at times, hit the mark. Which brings us to the second point: Demolition Man is oddly prescient in a number of ways.

At one point there’s what, at the time, was a throwaway joke about Stallone’s long-time cinematic rival Arnold Schwarzenegger becoming president. While that didn’t exactly come to pass, it does predict the Austrian body builder’s later political career. There was even an “Amend for Arnold” movement that pushing to amend the Constitution to allow a presidential run.

Not that there was no nostalgia before—the ‘80s were all about 1950s nostalgia. But Demolition Man also foresaw the coming wave of wistful societal longing for an earlier time that struck land roughly a decade later. In the early 2000s, pop culture took a long look at the ‘80s through rose-colored glasses (I drove a delivery van around that time and almost every radio station, no matter the genre, had an ‘80s lunch hour, or similarly themed throwback programming).

Demolition Man offers up a shining example of the type of “nostalgia film” social critic and philosopher Fredric Jameson talks about in his essay, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.”

In the same way Jameson talks about movies like Star Wars and Chinatown hearkening back to earlier eras, Demolition Man nods to dystopian novels like 1984, Fahrenheit 451, and especially Brave New World, which it overtly references.

Pre-celebrity Sandra Bullock plays a naïve, nostalgia-obsessed cop with the on-the-nose name of Lenina Huxley. Her moniker combines two names connected to the book—Lenina Crowne is a main character in Brave New World, which was written by Aldous Huxley. She longs for a past she never lived, that, like so many who pine for a bygone era, she only experienced through remnants of pop culture.

For his part, John Spartan is a throwback to an earlier era of law-enforcement. He’s often referred to as a savage by his future co-workers. This invokes the name of John Savage, or John the Savage, a character in Brave New World. Plucked from the squalor of the “Savage Reservation,” they’re both from an earlier time, or at least a place that approximates an earlier time, and live outside the new norms and mores. True to dystopian form, the Spartan/Savage character reveals this “perfect” future for what it is: flawed, corrupt, and built upon an unstable foundation.

Sylvester Stallone has had a long career, one full of a number of ups, downs, and resurgences. While his star wasn’t necessarily waning in 1993, the style of action that propelled him through the ‘80s had lost favor with audiences, and this was a strange place in his career. He was coming right off Cliffhanger, which rules and was a major hit, but this was also shortly after the debacles of Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot and Rocky V, and right before The Specialist and Judge Dredd. These weren’t all financial flops, but they all have… issues and were largely savaged by critics and viewers.

Demolition Man serves as a meta-meditation on the shoot-em-up tough guy persona Stallone cultivated for so long. It explicitly references First Blood and John Rambo, and Spartan is a carbon copy of any number of the renegade cops Stallone has played over the years. One podcast points out that he’s basically Marion Cobretti from Cobra, while noting that this hyper-idealized vision of the future is also Cobretti’s version of a nightmare. Spartan is an archetype Stallone character juxtaposed against an atypical backdrop, and the result is a fish-out-of-water story.

This was also right around the time the big indie movie boom was taking off in the early 1990s—Pulp Fiction blew the doors off theaters a year later in 1994. Cinematic expectations and interests were changing. In many ways, Demolition Man plays like the product of an out-of-touch studio system struggling to stay relevant. Their hive-mind approach had no real clue what audiences wanted and you can practically feel their desperation here as they throw everything at the wall to see what sticks.

That’s how Demolition Man wound up with things like Rob Schneider’s character, which was dated even before the movie came out. He’s more or less doing his Saturday Night Live Copy Guy, which was a meme before there were memes.

The same goes for Dennis Leary. Up to this point, he was mainly known as an edgy, underground comedian, but 1993 was the year he exploded. His album, No Cure for Cancer, came out in January and was a massive hit. He was everywhere. St one point in Demolition Man, everything stops and he launches into a monologue that is just his act.

Not without flaws, problems, and peculiarities, Demolition Man doesn’t deserve the tarnished reputation it has; it certainly doesn’t deserve to the butt of so many joke. (except for three seashells jokes, it earns every one of those). It kicks a lot of ass, is a ton of fun, and is smarter than it usually gets credit for, even if it doesn’t always realize that. And I’m always down for a rendition of the future envisioned by an earlier era, which so often illuminates where society’s collective mind was at that specific time.

This also might not be the last we see of Demolition Man on the big screen. In early May of 2020, Stallone did a Q&A on Instagram:

He broaches a number of topics, and when asked about the potential for Demolition Man 2, he said:

“Can we get another Demo Man? I think it is coming. We’re working on it right now with Warner Bros. and it’s looking fantastic. So that should come out, and that’s going to happen.”

Is this real? Is this just Stallone talking? Have there actually been discussions? Who knows how legitimate any of this is or what chance it actually has of becoming a reality. But with movies like Creed and Rambo, Sly’s certainly not opposed to revisiting earlier roles. And to be fair, I’d much rather see Demolition Man 2 than another Rambo movie.