Color Out Of Space: Movie Review

Hyper-stylized, strange and gooey, existential and mind-bending, and topped by a committed Cage performance, this is a wild detour into psychedelic sci-fi.

“Hyper-stylized, strange and gooey, existential and mind-bending, and topped by a committed Cage performance, this is a wild detour into psychedelic sci-fi.” –Brent McKnight, GiantFreakinRobot.com’s Color Out Of Space Review

Nicolas Cage has had a wildly varied career as an actor, and in the latest stage, it’s become straight up bizarre. Maybe he hunts a jaguar and an international assassin on a boat (Primal), or plays a trucker dating a woman whose daughter is possessed by the spirit of his dead wife (Between Worlds), or slaps on an absurd prosthetic nose (Arsenal). We have to wade through movies where he showed up on set for a week to collect a paycheck, like Running with the Devil, but he’s also turned in a near-career-best performance in Mandy, a movie where he happens to both battle demon bikers and remind us he has an Oscar for a very good reason.

Viewed from above, Color Out of Space feels like something of a peak or a culmination of all of Cage’s schizophrenic modern era career insanity. (Though to be fair, on the way he also has a movie where he uses martial arts to fight aliens, a tag team with Sion Sono he calls the wildest movie he’s ever made, and one where he plays a meta version of himself who battles a drug cartel for the CIA, so maybe the real madness is yet to come.) Cage teams with gonzo director Richard Stanley to adapt an H.P. Lovecraft story and the result is psychedelic and strange, tense and off-kilter, and gory as it builds towards a crescendo of chaotic mayhem.

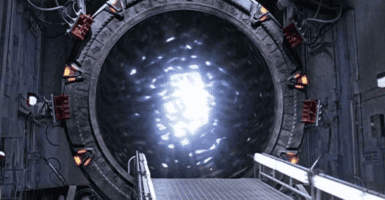

In Color Out Of Space, alpaca farmer Nathan Gardner (Cage) and his family—wife Theresa (Joely Richardson), daughter Lavinia (Madeleine Arthur), and sons Benny (Brendan Meyer) and Jack (Julian Hilliard)—live in a remote house in a small New England town. When a meteorite lands in their backyard, strange things happen. Odd events occur, unusual plants grow, people’s behavior changes, strange creatures appear, and the flow and rules of time no longer apply like they once did thanks to a malevolent alien presence.

If you’re unfamiliar with Stanley’s 1990 gonzo tech-thriller Hardware, check out Lost Soul, a documentary about his ill-fated attempt to make The Island of Dr. Moreau. It perfectly illustrates why he’s the ideal director to team with a fellow outsider iconoclast like Cage to adapt a sci-fi tinged Lovecraft story. And the finished product does not disappoint.

From the get-go in Color Out Of Space, Stanley evokes a world that’s both modern and anachronistic in multiple ways. A rich, purple-hued, near-Day-Glo color palate hearkens back to the 1980s, but the Lovecraftian flourishes nod to something much older and much more ancient. They call upon ideas of witchcraft, rituals, and deep old woods full of terror and mystery; houses are full of history, home to cryptic cellars, gothic attics, and various familial secrets.

Even before the meteorite, every bit of mood and atmosphere in Color Out Of Space undercuts the idyllic surface machinations. Theresa battles an illness no one talks about, they relocated to Nathan’s family home for shadowy reasons, and the kids all have their own troubles. From this early disquiet, Stanley and screenwriter Scarlett Amaris gradually ratchet up the pressure and the uncanny, bit by bit until it hits synapse-melting levels of hallucinatory paranoia.

Intricate time dynamics and narrative games combine with mechanical touches to aid the tension and unsettling ambience. Stanley and cinematographer Steve Annis use a lush, heightened color scheme and have an eye for unusual framings and angles that enhance the unreality. And when it comes to creature design and effects, Color Out of Space calls to mind movies like The Thing and Sam Raimi’s early movies, horrific monsters dripping with goo, gnarly and grotesque and alien.

Cage goes for it in Color Out Of Space, which isn’t uncommon, the man is fully committed, even when barely present. But this isn’t the meme-ified version so prevalent these days. He pushes himself to a raw, manic place, jacked-up and full-go. But it isn’t only him coming unhinged. Sure, he’s wild and overblown, screaming about Alpacas, but he also presents a nuanced and layered portrait of a man breaking on various fronts. Zipping from one end of the spectrum to the other, he comes unglued in terrifying, earnest, spectacular fashion.

Color Out of Space modernizes the story but still captures the tone and disposition of Lovecraft in a way that many other adaptations miss. The mask of normalcy that hides something much darker, much stranger is so key to his work and on full display here. And it’s only then, after establishing an underlying strangeness, that the real horrors begin. It’s also a smorgasbord of references for fans of the problematic writer, from obvious ones, like a character wearing a Miskatonic University sweatshirt, to smaller, subtler touches that should delight enthusiasts. All of this drives home the commitment and attention to detail of the filmmakers and their affinity for the source material.

Color Out of Space walks a fine line between methodical artistry and gonzo B-movie exploitation—don’t worry, this is still a movie that features Tommy Chong as an unhinged squatter who just kind of hangs out with Nic Cage’s teenage son. Hyper-stylized, strange and gooey, existential and mind-bending, and topped by a committed Cage performance, this is a wild detour into psychedelic sci-fi and horby ror.