Civil War Is An Insult To Your Intelligence

We’ve all felt it: the fear that, due to worsening frictions in our polarized society, some violent conflict will erupt. Thus, a film about a prospective civil war in modern America is, ya know, expected. But rather than bravely necessarily contend with some aspect of the political strife intensifying American life, Alex Garland’s new film shies away wholly, opting for a baselessly situated plot–a civil conflict without explanation or context.

Why Is It Even Happening?

By the end of his movie, you don’t know why the US is plunged into domestic war; and the main characters, who would have to compensate for this extreme lack of world-building with compelling, engaging characterization of their own, offer nothing but unrelenting flatness.

Civil War follows the journey of a group of war photographers from New York City to Washington, DC, hoping to photograph the president—who is on his third term and has committed a slew of atrocities (murdering journalists among them).

All of which amounts to a sort of fan fiction dedicated to grafting Apocalypse Now on Northern Virginia.

The Competing Sides

Indeed, the film’s fundamental flaw is that it fails to provide an explanation for why the United States is at war with itself.

Yes, it offers four factions—the Western Forces (an alliance of Texas and California, which is as unbelievable as it sounds), the Florida Alliance (basically the South), the New People’s Army (Midwest, Northwest), and Loyalist states (everybody else).

And if this unfinished AI printout of a plot in Civil War strikes one as half-baked, it is. If it feels like an effortless half-stab at lore development before an early lunch—yep.

Terrible World-Building

Indeed, we don’t know why Texas and California, such utterly different states, have united to form the Western Forces. We don’t know why the Florida Alliance formed, or their goals. The New People’s Army? Equally mysterious.

And by mysterious, I mean unfounded, unjustified, and unacceptable. A woeful excuse for world-building.

When surrendering soldiers and civilians are summarily executed, which happens in the film often enough, you have to ask–and you’re right to ask–why? Why the animosity, the atrocities, the shirking of the Geneva Convention? What motivates any of it?

Civil War should, at the end of the day, supply an answer.

But it doesn’t want to; it doesn’t want to offend. However, when you’re apologizing to eggshells before tiptoeing over them, yet you’re making a film about civil war in modern America–what results will assuredly be uninteresting.

Photography Team Isn’t Enough

Civil Wars, after all, are fought along extremely hard and irreconcilable ideological lines: pro-slavery or anti-slavery (America), pro-fascist or anti-fascist (Spain), pro-communist or pro-democracy (Russia), etc.

The point is that you have a reason for going out, brandishing a gun, and ending the lives of your fellow citizens while risking your own. This impetus needs to be incredibly motivational, more so than in armed conflicts that aren’t between people with the same passports.

And I’m sorry, but there’s not much to praise about the war photographer cast: Kirsten Dunst, playing a veteran of armed conflicts, offering the “I’ve seen it all, I’m dead inside” vibe and little else; Wagner Moura, as her less dead-eyed colleague; and young Cailee Spaeny, portraying the wannabe war photog (her arc from green novice to numbed receptacle of PTSD is the film’s cliched arc).

All Are Set Pieces, Not Characters

Ultimately, none are characters—rounded, relatable, credible personalities. They are instruments, set pieces.

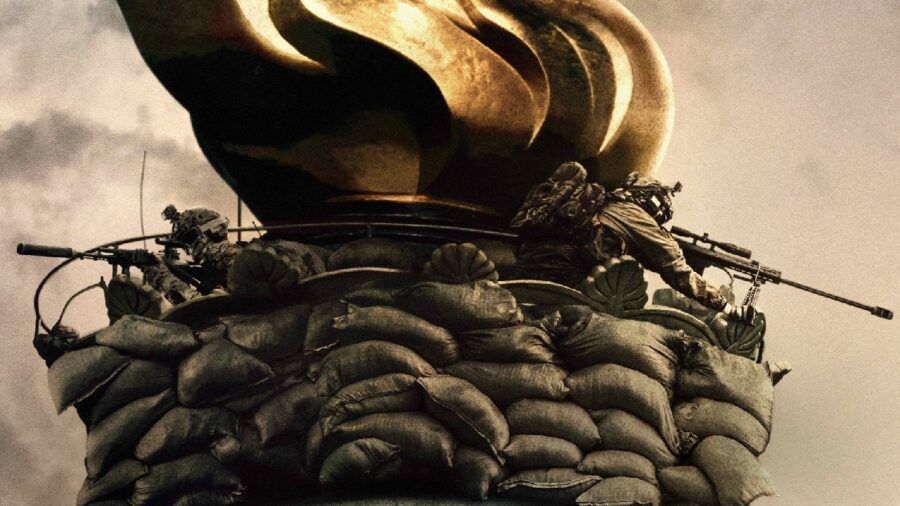

At the bottom, the Civil War and its characters constitute an empty shell meant to justify scenes depicting modern, conventional armed conflict in the US, but nothing more. It’s a means to an end, the end being sniper duels somewhere off I-95, mass shootings of prisoners of war, and combat helicopters spraying tracer rounds outside the White House.

A feature film dedicated to: “Wouldn’t it be cool if we there was a scene of—[insert war scenario]—in the 2020’s US?”

To be fair, though, the film looks great and obviously benefited from commendable direction and cinematography. It’s like an impressive, even beautiful house which, once you walk in, you realize contains no furniture, has no electricity, and even lacks flooring in some places, exposing the dirt floor beneath.

Refusing To Pick A Side

Again, this largely stems from Civil War’s refusal to pick a side. To tie any of the four military factions to any political cause or, barring that, to source their brutal crimes against humanity in any event or historical context.

And it’s not like US history lacks a basis or background for referencing civil conflict. A particularly realistic and useful period from history, for example, would not be the civil war between the Union and Confederacy, but a conflict immediately preceding it: Bleeding Kansas.

Then, a soon-to-be-a-state, the Kansas Territory, was bitterly and violently divided along the lines of whether to adopt slavery or reject it.

Needed More Realistic Context

REVIEW SCORE

In a struggle literally embodying good vs. evil, armed militia groups fought a guerilla campaign across this lawless midwest region; anti-slavery, abolitionist paramilitary units would ambush and massacre would-be slave-owners; slave-owning Southerners, armed to the teeth, would trek up to Kansas, and do the same to abolitionists, or rumored abolitionists.

It was chaos, with the US government, itself about to implode in the coming Civil War, deeply challenged as to how to respond.

This teetering, near-war would be a more realistic context for a modern incarnation. It would make more sense than four, more or less indistinguishable armies, from sloppily, lazily divided regions, waging a war in which all are equally well armed and equally pointless.

Ultimately, I get Garland’s desire to remain politically neutral and depict the horrors of war without offending anybody. But, again, that’s a surefire way to make an uninteresting film.

In other words: Civil Bore.

Skip it.