Nearby Planet Hiding Underground Ocean

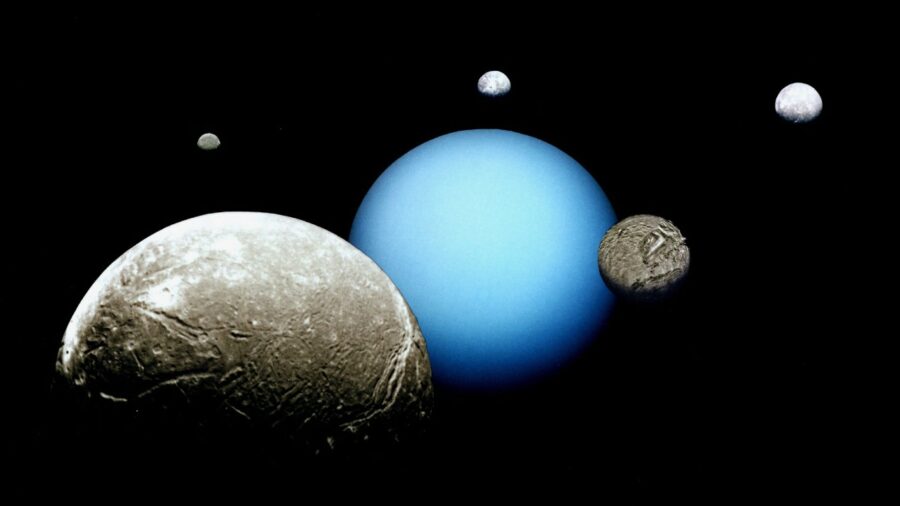

Uranus may be the butt of just about every space-related joke out there, but following a recent discovery, scientists are now keeping all of the jokes to themselves. While utilizing the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have discovered that Ariel, one of Uranus’ 28 moons, may in fact have an underground ocean of water stored right below its surface. The ocean could explain one mystery that has remained unsolved for years.

The Circumstances That Make it Possible

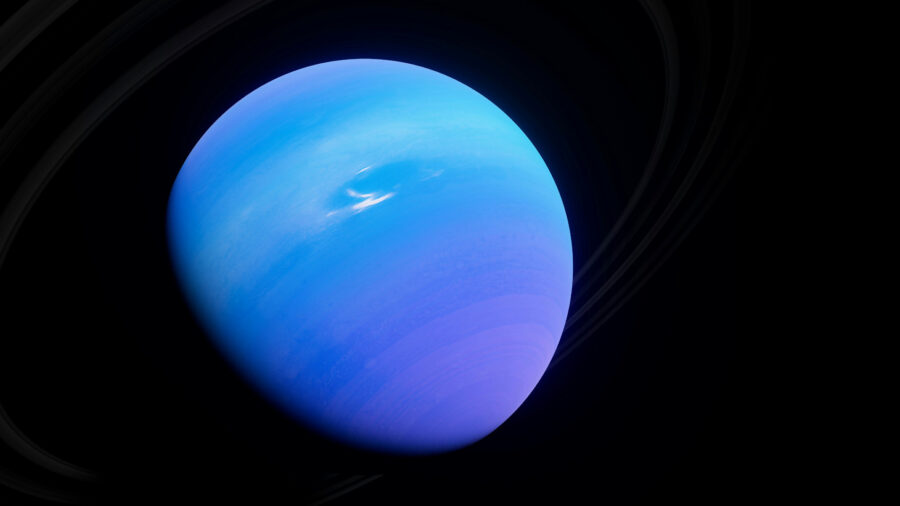

On average, Uranus is about 1.8 billion miles away from the sun throughout its orbit. In comparison, Earth is just 94.3 million miles away from the sun. That is roughly 20 times closer than Uranus.

With such a great distance between the planet and the sun, it takes nearly three hours for sunlight to reach Uranus and its surrounding moons. That distance contributes to an average surface temperature of -224 degrees Fahrenheit on Ariel, which is consistently covered with a layer of carbon dioxide ice. However, at such low temperatures, carbon dioxide turns to gas and escapes into the far reaches of space.

The Interaction Between Uranus And Its Moons

So how is that layer of carbon dioxide ice being replenished? Scientists have often theorized that interactions between the moon’s surface and charged particles in Uranus’ magnetosphere are creating carbon dioxide. They believed this was created through a process called radiolysis, in which molecules are broken down by ionizing radiation.

Scientists Can’t Fully Explain It

However, according to a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the answer to carbon dioxide may lie within the moon. This new theory suggests that the production of carbon dioxide could be the result of an underground ocean. While using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to collect the chemical spectra of the moon, a research team led by Richard Cartwright of Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory found that Ariel boasts an added 10 millimeters of thickness to its ice layer.

Within that layer of ice are some of the most carbon dioxide-rich deposits in the solar system. Further adding to the mystery of the moon was the discovery of carbon monoxide for the first time.

Cartwright outlined the surprise of his team’s findings. “It just shouldn’t be there. You’ve got to get down to 30 kelvins [-405 degrees Fahrenheit] before carbon monoxide’s stable,” he said. “The carbon monoxide would have to be actively replenished, no question.”

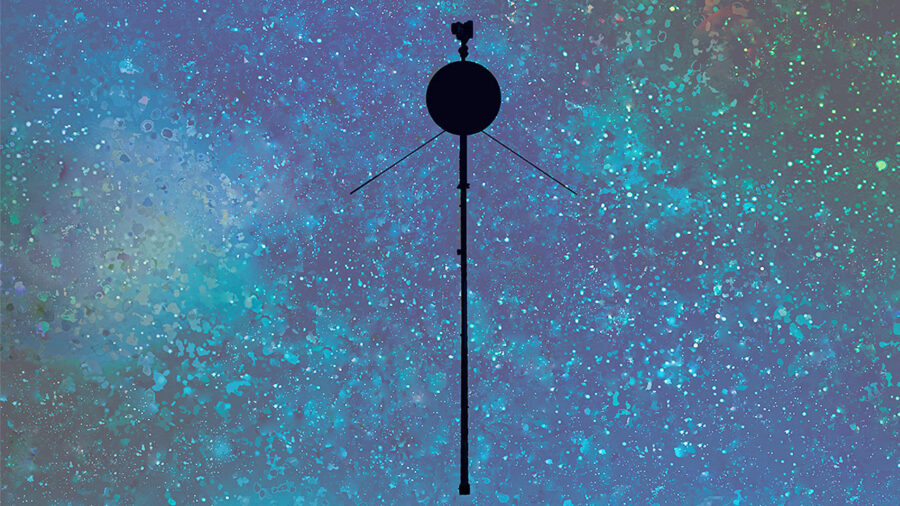

Still Benefitting From Voyager

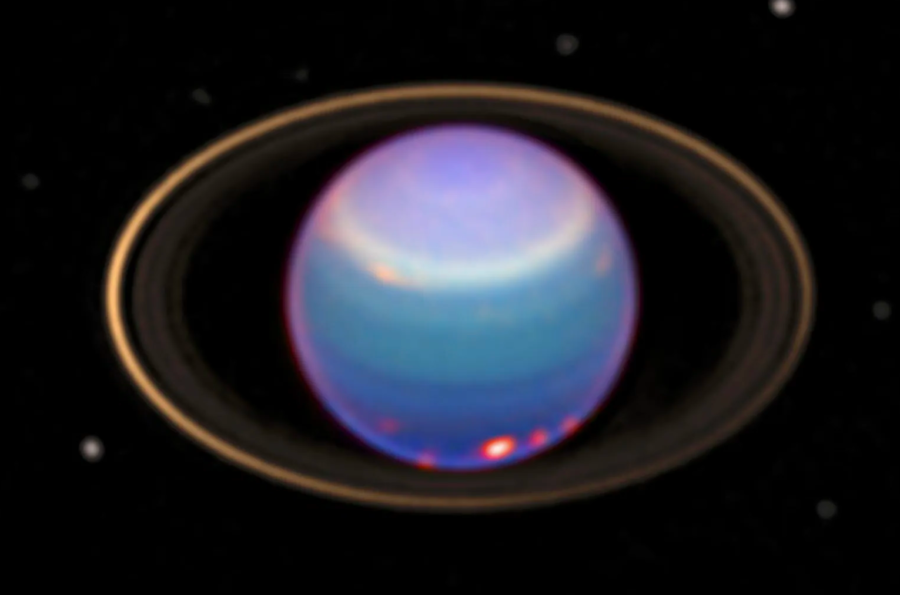

While the underground ocean of water could be the most logical theory, Cartwright hasn’t completely ruled out radiolysis. However, thanks to Voyager 2’s 1986 journey, researchers learned that the effect of radiolysis could be limited. Uranus’ magnetic field axis and the orbital plane of its moons are offset from each other by roughly 58 degrees.

With the limitation of radiolysis, a large portion of the carbon compounds discovered on Ariel’s icy surface could be from the chemical processes of a liquid ocean located under the ice. After being created in the underground ocean, the carbon oxides may then escape through cracks in the ice. Another exciting possibility is the theory of the existence of icy volcanoes.

A Different Type Of Volcano

Instead of these volcanoes emitting lava, they could spew a slurry of a frozen carbon mixture. With explosive eruptions, these volcanoes could even send their material hurtling into Uranus’ magnetic field. However, the majority of the cracks on Ariel’s surface are on the side facing away from the surface of Uranus.

Regardless of how Ariel’s carbon dioxide ice layer is replenished, Cartwright applauds his team’s discovery. “If our interpretation of that carbonate feature is correct, then that is a pretty big result because it means it had to form in the interior,” Cartwright said. “That’s something we absolutely need to confirm, either through future observations, modeling, or some combination of techniques.”