Scientists Predict Earth Becoming Barren Wasteland, Here’s How Long We Have

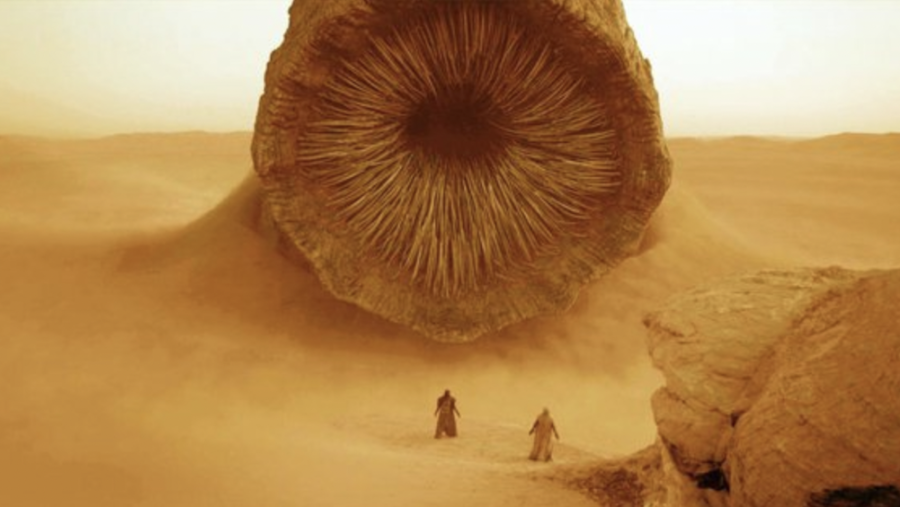

A groundbreaking, newly released study (via Futurism), spearheaded by the University of Bristol, bears some not-so-good news: we have 250 million years (give or take) until the Earth looks less like the “pale blue dot” we all know and love and more…like Arrakis, from the Dune Universe.

That’s right—the planet’s land masses seem to be slowly but surely congealing into one humongous supercontinent, at least according to the data returned from the University of Bristol’s high-powered climate model. Their study, formally published in the science journal Nature Geosciences, anticipates the continental merger will eventuate a globe-sized, one-continent-fits-all “Pangea Ultima.”

A super-continent that will, in addition to being unfathomably large, also be unimaginably hot. How hot?

The planet’s land masses seem to be slowly but surely congealing into one humongous supercontinent, referred to as Pangea Ultima.

Scorching enough to prohibit life for almost all mammalian organisms. In such an environment, it is hard not to imagine the inhabitants of Earth taking cues from the Fremen of Arrakis. And while there might not be sandworms the size of skyscrapers, the planet’s carbon dioxide levels will potentially double, given the anticipated volcanic activity and widespread tectonic shifting.

All of which would culminate in a planet more or less uninhabited by life—or at least warm-blooded life.

According to a press release by the University of Bristol regarding their disconcerting study, the university’s state-of-the-art climate simulation supercomputer revealed that our planet’s average temperature is projected to exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the formation of Pangea Ultima. This temperature rise is attributed to the abovementioned release of CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere and preceding flurry of volcanic activity.

The Sun–if you’re in the mood for more good news–will also become 2.5 percent brighter as Pangea Ultima takes shape, meaning an uptick in solar radiation and subsequent terrestrial heat. In such an environment, animal and plant life—fauna and flora—will struggle to survive.

Scientists at the University of Bristol predict that Earth will no longer be habitable in 250 million years.

While the developments might seem nearly surreal and impossibly far-off, they nonetheless represent significant implications for our distant descendants. Responding to his own work, lead study author Alexander Farnsworth voiced a rather bleak take on humanity’s potential future.

The scientist foresees human beings, adapting to the planet’s radical changes, resorting to nocturnal living or seeking shelter in Earth’s caves. Ultimately, Farnsworth’s sentiment aligns more with securing an alternative planet to inhabit—instead of trying to adjust to the uber-hostile conditions of Pangea Ultima.

And although the findings might sound like a plot straight out of Dune, the idea that our planet undergoes gargantuan changes over time is by no means novel (no pun intended). Hannah Davies, a German geologist unassociated with the study, emphasized how our planet has undergone many extinction events in its long history. She insisted life on Earth will doggedly find a way—even if it means navigating through a grim epoch.

The university’s state-of-the-art climate simulation supercomputer revealed that our planet’s average temperature is projected to exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the formation of Pangea Ultima.

Notably, the University of Bristol’s modeling excluded factoring in human-induced carbon emissions. Not to make things more pessimistic—but including carbon emissions, even hypothetically, would suggest potentially hastened, or worsened, forecasted outcomes.

Sure, the timespan of these catastrophic events stretches millions of years into the future. But the study nonetheless serves as a stark reminder of the profound and lasting changes Earth undergoes. While also—on a brighter note—underscoring the resilience of life to adapt.