Why Some Moments Last Longer Than Others: Uncovering The Secrets Of Passing Time

You may think you can tell how long a minute is, but there’s no direct correlation between a spot in our brain and how we perceive time. The human mind is an accurate timekeeper but not consistent; despite our ability to keep a beat or hit a baseball, there’s just no telling how long we’ll believe the event lasted.

Researchers are trying to figure out why the last two hours of school before summer vacation appear to drag on forever.

No one truly knows how it is that the last two hours of school before summer vacation appear to drag on forever. Time itself does not adhere to the ticking of a clock; it’s a gossamer thread just out of view that you can’t quite capture. However, researchers have been trying to figure it out, and a study in Proceedings of the Royal Society posits that neurons may be involved in how humans perceive the passage of time.

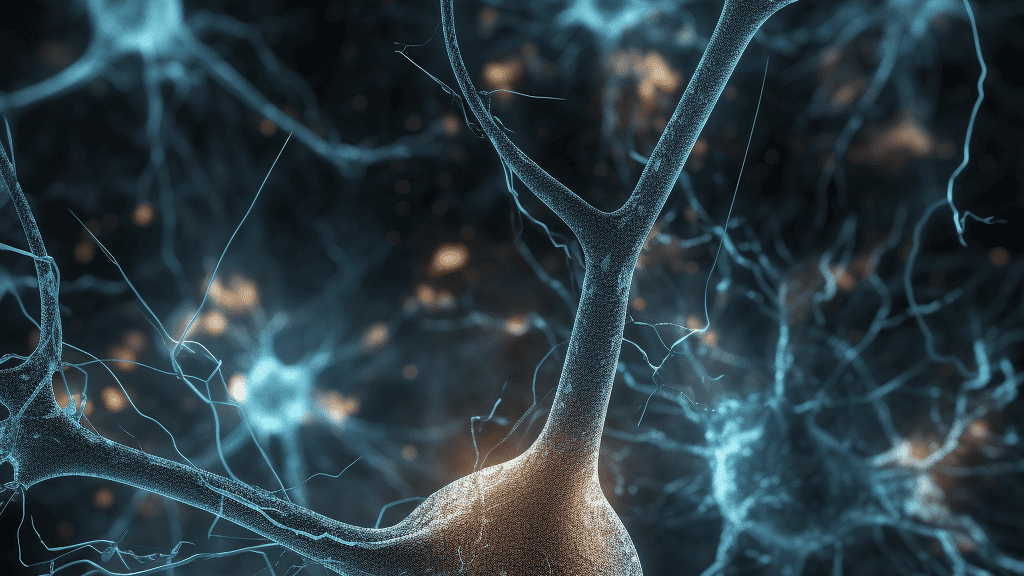

Evidence strongly suggests the presence of neural units in the brain that are tuned to different durations.

“We know the brain [tracks time] routinely and accurately, but we’re not sure how,” said the lead author of the study, James Heron of the University of Bradford in the United Kingdom. “Our evidence strongly suggests the presence of neural units in the brain that are tuned to different durations.” While we have a greater understanding today of how spatial reasoning works in the brain, no real progress has been made in temporal reasoning.

Neuron channels respond and become accustomed to a frequency of time

The research team believes that neuron channels respond and become accustomed to a frequency of time, and that these channels may be at least partially responsible for how time passes in our minds. Using sensory adaptation the team was able to show that the main neuron channel was adjusted to what would be the base sense exposure.

In this case, it was a 100 percent contrast isotropic Gaussian luminance blob and white noise played through Sennheiser HD 280 headphones administered at an interval of 150 milliseconds.

Participants were asked to discern which signal was longer when two were displayed in succession.

Participants were exposed to these auditory and visual signals and then were asked to discern which signal was longer when two were displayed in succession. When the signal was closer to the adapted one, participants were further off in their guesses. A reciprocal pattern is found as the duration moves further from the baseline adapted signal length. Heron thinks that those neuron channels could be “fresher” and able to more accurately keep time.

A wandering, unfocused, mind may be too preoccupied with how time is passing.

So what does this mean? It doesn’t answer the question of how some moments last so long. But it lets us guess at the reasoning, and if adapted sensory does play a part in temporal reasoning, then it could be assumed that a wandering, unfocused mind during those aforementioned last hours of school may be too preoccupied with how time is passing with each glance at the clock. Staying focused on a task seems to help alleviate the dragging of time.