Prince’s Estate Censors Another Singer From Using His Own Name

Prince's estate is legally blocking a famous singer from using the name they've performed under for 40 years, and they aren't having it.

This article is more than 2 years old

In 1993, the artist born Prince Nelson Rogers made what was widely considered a bizarre and ridiculous move. He changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol and announced that he was no longer to be referred as Prince, but as the Artist Formerly Known as Prince. The press conference he gave around that time, in which he appeared with the word “slave” written across his cheek probably did not help. He resumed using his own name (which, to be clear, was not a stage name, but his actual name) in 2000, and by the time of his tragic passing in 2016, had regained his position as one of the most revered pop musicians in the world. All of this just makes it that much more sadly ironic that after his death, his estate is now preventing his friend, rival, and protege Morris Day from using the band name “The Time.”

The matter is not wholly different from Prince’s name change, which was later re-evaluated as a shrewd, if oblique tactic against Warner Bros, the record label that legally owned the rights to “Prince” as the name of a recording artist. Now, the positions are reversed, and Prince’s estate (which is controlled by three of his surviving siblings and the music publishing company Primary Wave) is stating that they have legal ownership of the name “The Time” and Morris Day has no right to use it. The singer of “Jungle Love” and “The Bird” has performed, recorded and toured using The Time as the name of his backing band. However, according to a letter to his attorney from the estate, that name has been under sole ownership of Prince (and by extension, now his estate) since 1982.

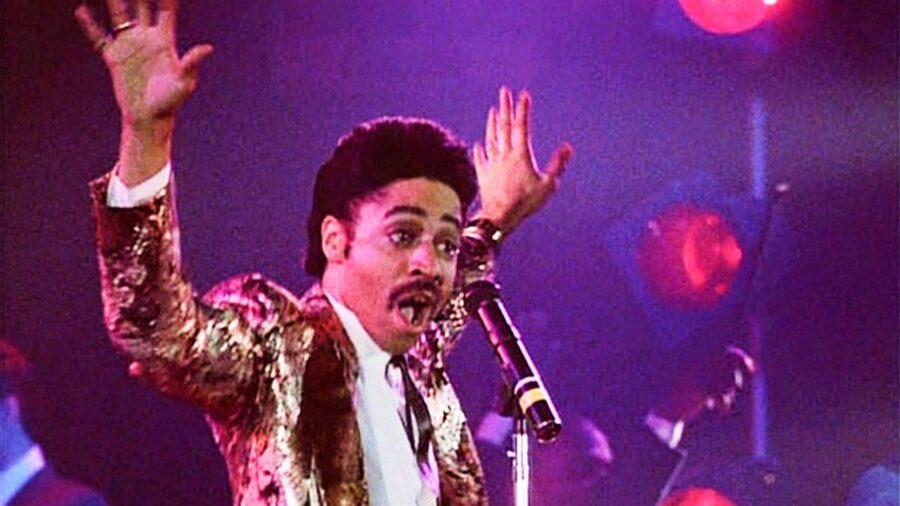

For his part, Morris Day does not dispute the fact that Prince owned the name. Among the many unique industry maneuvers by Prince, he would essentially manufacture musical groups and singers to act as extensions of his musical (and financial ideas). In its earliest incarnation, Prince formed The Time to essentially perform the kind of funk R&B that he had increasingly little interest in. Their early albums were performed and produced entirely by Prince, with the exception of Day’s vocals. He would go on to use them as a support act on tours, and have them portray a rival musical group to his own in his 1984 film Purple Rain. But Day’s complaint is that Prince himself never denied him the right to use the name, and by implication, the estate is acting in bad faith by doing so.

Prince’s estate initially denied that they had prevented Morris Day from using the name, but later stated they were open to negotiating his future use of it (read: more money). And while Day is largely correct that he has used the name for 40 years, Prince himself did at one point briefly force a name change on them. Show business law is an enormously complicated thing, and the ownership of intangible concepts is hard to parse. Just look at director Quentin Tarantino’s struggles with Miramax over who can do what with his film Pulp Fiction, or the clash between Warner Bros and Travelling Roadshow over how to release the films they jointly make. It is difficult to say how this will turn out, but hopefully Morris Day will be performing again as soon as possible.